Posted initially on Aug 5, 2016

Interview by Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer

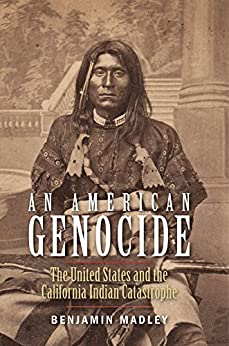

“Benjamin Madley1 has changed the conversation on genocide and American Indians. After An American Genocide, it will no longer be possible to debate whether or not genocide took place. Instead we will need to confront the questions of how and why genocide against American Indians took place and what the United States owes its indigenous communities.”—Karl Jacoby (Columbia University), author of Shadows at Dawn: A Borderlands Massacre and the Violence of History

WN: What we read about in this article, based on meticulous research by Californian historian Benjamin Madley, in his book An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873 is utterly tragic and far beyond reprehensible. There is a similar story to be told about Native Americans in many other places and times by actions of the various levels of government in the United States, not to mention similar stories throughout the world, in particular during the time of the United States Empire in the twentieth century to this present day. This is also what has characterized “American exceptionalism” at all times of its history.

WN: What we read about in this article, based on meticulous research by Californian historian Benjamin Madley, in his book An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873 is utterly tragic and far beyond reprehensible. There is a similar story to be told about Native Americans in many other places and times by actions of the various levels of government in the United States, not to mention similar stories throughout the world, in particular during the time of the United States Empire in the twentieth century to this present day. This is also what has characterized “American exceptionalism” at all times of its history.

A random example, from one of my Book Reviews, featuring in part John Kerry:

“ ‘For seven months, Tiger Force [one of countless American units during the Vietnam War, fully authorized by superiors all the way up the chain] soldiers moved across the Central Highlands, killing scores of unarmed civilians – in some cases torturing and mutilating them – in a spate of violence never revealed to the American public,’ the newspaper said, at other points describing the killing of hundreds of unarmed civilians.

“ ‘Women and children were intentionally blown up in underground bunkers,’ The Blade said. ‘Elderly farmers were shot as they toiled in the fields. Prisoners were tortured and executed – their ears and scalps severed for souvenirs. One soldier kicked out the teeth of executed civilians for their gold fillings.” The New York Times confirmed the claimed accuracy of the stories by contacting several of those interviewed. It reported: “But they wanted to make another point: that Tiger Force had not been a ‘rogue’ unit. Its members had done only what they were told, and their superiors knew what they were doing.

“Burning huts and villages, shooting civilians and throwing grenades into protective shelters were common tactics for American ground forces throughout Vietnam, they said. That contention is backed up by accounts of journalists, historians and disillusioned troops…

“ ‘Vietnam was an atrocity from the get-go,’ [one veteran] said in a recent telephone interview. ‘It was that kind of war, a frontless war of great frustration. There were hundreds of My Lais. You got your card punched by the numbers of bodies you counted.’ (Kifner, 2003).”

Current [then] likely Democratic Presidential candidate John Kerry was also quoted giving evidence before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1971. He reported that American soldiers in Vietnam had “raped, cut off heads, taped wires from portable telephones to human genitals and turned up the power, cut off limbs, blown up bodies, randomly shot at civilians, razed villages in fashion reminiscent of Genghis Khan, shot cattle and dogs for fun, poisoned food stocks and generally ravaged the countryside of South Vietnam in addition to the normal ravage of war, and the normal and very particular ravaging which is done by the applied bombing power of this country (quoted in Kifner, 2003).”

Please also see, ERIN BLAKEMORE, California’s Little-Known Genocide: Up to 16,000 Native Americans were murdered in cold blood after California became a state. We read:

“Gold! Gold from the American River!” Samuel Brannan walked up and down the streets of San Francisco, holding up a bottle of pure gold dust. His triumphant announcement, and the discovery of gold at nearby Sutter’s Mill in 1848, ushered in a new era for California—one in which millions of settlers rushed to the little-known frontier in a wild race for riches.

But though gold spelled prosperity and power for the white settlers who arrived in California in 1849 and after, it meant disaster for the state’s peaceful indigenous population.

In just 20 years, 80 percent of California’s Native Americans were wiped out. And though some died because of the seizure of their land or diseases caught from new settlers, between 9,000 and 16,000 were murdered in cold blood—the victims of a policy of genocide sponsored by the state of California and gleefully assisted by its newest citizens.That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected . . . —Peter Hardenman Burnett, the state’s first governor

Today, California’s genocide is one of the most heinous chapters in the state’s troubled racial history, which also includes forced sterilizations of people of Mexican descent and discrimination and internment of up to 120,000 people of Japanese descent during World War II. But before any of that, one of the new state’s first priorities was to rid itself of its sizeable Native American population, and it did so with a vengeance.

Local governments put bounties on Native American heads and paid settlers for stealing the horses of the people they murdered.California’s native peoples had a long and rich history; hundreds of thousands of Native Americans speaking up to 80 languages populated the area for thousands of years. In 1848, California became the property of the United States as one of the spoils of the Mexican-American War. Then, in 1850, it became a state. For the state and federal government, it was imperative both to make room for new settlers and to lay claim to gold on traditional tribal lands. And settlers themselves—motivated by bigotry and fear of Native peoples—were intent on removing the approximately 150,000 Native Americans who remained.“Whites are becoming impressed with the belief that it will be absolutely necessary to exterminate the savages before they can labor much longer in the mines with security,” wrote the Daily Alta California in 1849, reflecting the prejudices of the day.

They were assisted by the government, which considered the so-called “Indian Problem” to be one of the biggest threats to its sovereignty. The legal basis for enslaving California’s native people was effectively enshrined into law at the first session of the state legislature, where officials gave white settlers the right to take custody of Native American children. The law also gave white people the right to arrest Native people for minor offenses like loitering or possessing alcohol and made it possible for whites to put Native Americans convicted of crimes to work to pay off the fines they incurred. The law was widely abused and ultimately led to the enslavement of tens of thousands of Native Americans in the name of their “protection.”

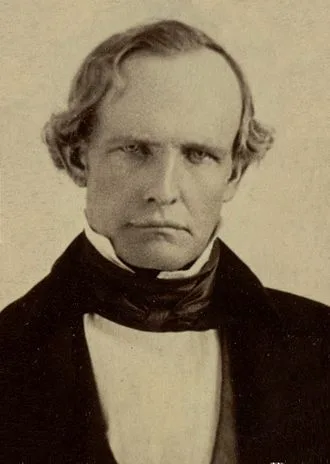

Portrait of The Representative Ugly American Statesman

This was just the beginning. Peter Hardenman Burnett, the state’s first governor, saw indigenous Californians as lazy, savage and dangerous. Though he acknowledged that white settlers were taking their territory and bringing disease, he felt that it was the inevitable outcome of the meeting of two races.

“That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected,” he told legislators in the second state of the state address in 1851. “While we cannot anticipate this result but with painful regret, the inevitable destiny of the race is beyond the power or wisdom of man to avert.”

Burnett didn’t just refuse to avert such a conflict—he egged it on. He set aside state money to arm local militias against Native Americans. The state, with the help of the U.S. Army, started assembling a massive arsenal. These weapons were then given to local militias, who were tasked with killing native people.

Whites are becoming impressed with the belief that it will be absolutely necessary to exterminate the savages before they can labor much longer in the mines with security.—Daily Alta California in 1849State militias raided tribal outposts, shooting and sometimes scalping Native Americans. Soon, local settlers began to do the killing themselves. Local governments put bounties on Native American heads and paid settlers for stealing the horses of the people they murdered.“By demonstrating that the state would not punish Indian killers, but instead reward them,”writes historian Benjamin Madley2, “militia expeditions helped inspire vigilantes to kill at least 6,460 California Indians between 1846 and 1873.” The U.S Army also joined in the killing, Madley notes, killing at least 1,600 native Californians.

Large massacres wiped out entire tribal populations. In 1850, for example, around 400 Pomo people, including women and children, were slaughtered by the U.S. Cavalry and local volunteers at Clear Lake north of San Francisco. One of the few survivors was a six-year-old girl named Ni’ka, who stayed alive by hiding in the lake and breathing through a reed.

Meanwhile, white settlers and the California government enslaved native people and forced them to labor for ranchers through at least the mid-1860s. Native Americans were then forced onto reservations and their children forced to attend “Indian assimilation schools.”

An estimated 100,000 Native Americans died during the first two years of the Gold Rush alone; by 1873, only 30,000 indigenous people remained of around 150,000. According to Madley, the state spent a total of about $1.7 million—a staggering sum in its day—to murder up to 16,000 people.

Large massacres wiped out entire tribal populations. In 1850, for example, around 400 Pomo people, including women and children, were slaughtered by the U.S. Cavalry and local volunteers at Clear Lake north of San Francisco.

The “white man’s burden” has ever been the white man’s horror, or the white man’s alibi, or the white man’s curse, or the white man’s mass murder, or the white man’s greed, or the white man’s fear, or the white man’s racism, or the white man’s hate, or the white man’s militarism, or the white man’s militaristic capitalism, or the white man’s imperialism, or the white man’s… (fill in the blank with anything nasty, avaricious and brutal).

And of course, one question is begged throughout this era:

Who were the real “savages?”

P.S. There is also a Canadian story. See for instance here.

excerpts:

RS: I’m talking to really an unusual academic, Benjamin Madley, who teaches history at UCLA. While he holds to all of the great academic standards of documentation and so forth, there’s a real passion and a sense of righting wrong in this book, An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873 (The Lamar Series in Western History), that actually raises a very fundamental, profound criticism of the entire American experience. Because if, after all, right at the heart of that experience we had genocide, you have to come to grips with it. What kind of people, God-fearing people, would engage in the wholesale elimination of another people? And one way you accept that, as you’re living through it, is to think of them as “savages.” Now, your father was a man of the mind, right? And why don’t you tell us a little about your father and to what extent he inspired this work, and helped you understand the complexity of a people that we committed genocide against?

…

One important reason to read your book is as a corrective to this history that we pay lip service to, of you know, the city on the hill that Ronald Reagan talked about; the unique American experience. And here we’re in a presidential election where Donald Trump wants to make America great again, and Hillary Clinton says it’s always been great and is great, and so forth. And then you come along with a book—I don’t know why I’m making, I don’t mean to make light of it; genocide is genocide—but you come along with a book in this season of American celebration once again, saying yes, but in the middle of this great experiment, and the creation of the city on the hill, there was something called genocide.

BM: One of the issues that comes up for all of us, if we call something genocide in the history of the United States, something driven by state and federal authorities quite explicitly and intentionally, is that we have to rethink the assumption that the United States is exceptional. So this challenges the idea of American exceptionalism.

RS: You have mentioned journalists now several times as sort of culprits in this; now we can add government officials, political leaders. And I think it’s important to make that point, because otherwise reading a lot of the specific incidents in your book, one could think, oh, there’s that crazy guy and there’s that killer and there’s that hired gunman, you know. And there are a lot of nasty killers that were recruited by companies, by landowners, by others, to terrorize Indians. And yet they were backed by respectable society. So let’s begin with journalists. Tell me about the reporting on all this.Simon Kuper notes in the Financial Times that [Boris] Johnson’s net favorability rating collapsed from +29 percent in April 2020 to -52 percent in January 2022. “Here, in microcosm,” Kuper writes, “is the uniqueness of American polarisation”: Those who favor Trump are bound to him as with hoops of steel, come what may. This total indifference to evidence is today’s “American exceptionalism.”—George F. Will

Because if, after all, right at the heart of that experience we had genocide, you have to come to grips with it. What kind of people, God-fearing people, would engage in the wholesale elimination of another people? And one way you accept that, as you’re living through it, is to think of them as “savages.”BM: These things, whether they were massacres, murders, or whole killing campaigns that went on for months, were hidden in plain sight. You need only start by reading the many newspapers of the period to read about these things in detail. U.S. army officers’ reports were often published in newspapers; militia officer reports were likewise published in newspapers; and eyewitnesses, whether deploring the killing or celebrating it, routinely wrote in to the newspapers to report these things, and editors then commented on them. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that state legislators assembled and then expanded a state-sponsored killing machine. California governors called out or authorized no fewer than 24—that’s two dozen—state militia campaigns against California Indian people, that killed at least 1,340 of them. That state legislature played a key role in the killing campaign, by then funding these operations; they raised over $1.51 million to fund them. The federal government, in turn, then supported the state of California by refunding to the state almost all of the money that the state spent on the killing. At the same time, the U.S. army was often involved in killing or massacring California Indians, from 1846 when they first massacred California Indians at the Sacramento River, under John C. Fremont and Kit Carson, and only concluding in 1873 when they ended the Modoc War by decapitating four of the leaders and sending their severed heads to Washington.…

RS: But what about the most shocking stuff that you talked about before, throwing babies into fires and bayoneting and so on? Would that have been commonly, knowledge that was commonly available?

BM: Yes. Often, the reports consist of only a line or two. They tell us the number of people who were killed, where they were killed, and perhaps why they were killed. In most instances, we don’t get those really gruesome details. But I’ll tell you, I had to cut a lot of detail out of this book. Believe it or not, it was much larger before we began to trim it down, and a lot of what I removed were those gruesome details that I thought didn’t need to be repeated in every instance.These things, whether they were massacres, murders, or whole killing campaigns that went on for months, were hidden in plain sight. You need only start by reading the many newspapers of the period to read about these things in detail. U.S. army officers’ reports were often published in newspapers; militia officer reports were likewise published in newspapers; and eyewitnesses, whether deploring the killing or celebrating it, routinely wrote in to the newspapers to report these things, and editors then commented on them.

…

RS: What I’m trying to understand is, was this a case, again, that “the other” were thought to be subhuman and not warranting respect? I mean, and in terms of religion, it would seem to be a specific denial of what, say, Jesus Christ was about. After all, missionaries had started this practice, and here was Jesus telling us about “the other” and the Good Samaritan and Luke and so forth. How did they handle all this? How did they handle this dismissal of the human quality? I mean, to throw a baby into the fire? In America? That’s not part of our history that many people have talked about, including other respectable historians.

BM: One of the things that I take away from this book, which was very difficult to write, is that there is no safe level of racism. Racism is the fundamental idea that has to be ingested in some shape or form by the killers in order to carry out mass murder, in order to carry out genocide. But genocide is too big a project to be extemporized by individuals unconnected to a state or some larger group and organizing principles. What we see in California is that the state, both state and federal officials, utilized that rhetoric of dehumanization in order to convince soldiers, militiamen, and vigilantes that what they were doing was not only proper, but was morally laudable. So U.S. army officers who carried out and directed massacres were not punished; rather, they were rewarded and promoted and pushed up in the ranks. That is part of what is necessary to make a genocide happen. Because individuals, most of us, are incapable of doing this kind of thing over and over again unless there is an authority and an ideological framework that rewards and supports us for doing these things.

RS: So let’s just be clear about one thing, because this came up in the German genocide. You know, who were the good Germans and did they know? And there were plenty of people that said no, we didn’t know; if we had known, we would be shocked, and so forth. And of course that turns out not to be the case; if you didn’t know, it’s because you didn’t want to know. They clearly knew people were being rounded up. So what about the good Californians?

What I’m trying to understand is, was this a case, again, that “the other” were thought to be subhuman and not warranting respect? I mean, and in terms of religion, it would seem to be a specific denial of what, say, Jesus Christ was about. After all, missionaries had started this practice, and here was Jesus telling us about “the other” and the Good Samaritan and Luke and so forth. How did they handle all this? How did they handle this dismissal of the human quality? I mean, to throw a baby into the fire? In America? That’s not part of our history that many people have talked about, including other respectable historians.BM: There were people in all walks of life who protested the horrors of the genocide that they saw all around them, and who took steps to try to stop it. Officers from the Office of Indian Affairs, United States army officers, even militia commanders; they saw that what was happening was wrong, and every instance where I found white people objecting to the genocide, I tried to underscore and put them into the book, in part because I wanted to reward them for taking what was a dangerous stand, but also in order to clearly mark the fact that there were people who knew, then, that this was wrong. There was a U.S. army officer who told the militiamen that if they came to the Fort Crook area, that he would shoot them; that they would not only find women and children to confront, but that they would find U.S. soldiers to confront. There was a woman outside of what is now Redding, California, who when the killers, the killing squads came to her house, stood in front of three Indian women that she employed and held a quilt in front of them. And she was pregnant. She said to the killers, if you want to kill them, you have to kill me also. Real heroes then intervened; they took the women away in a wagon, far to the west, where they could be safe. But the sad truth is that there weren’t enough people who stood up for California Indians amidst the carnage. The truth is that it was an anti-Indian state legislature, and an anti-Indian United States Congress that won the day.RS: I’m talking to Benjamin Madley, concluding an interview with Benjamin Madley, who wrote An American Genocide. I dare say it’s the most powerful indictment of our society in terms of its racist history and its treatment of “the other”; it’s compelling. Will it be ignored? What’s the response?

BM: Well, the response so far has been far beyond anything that I could have imagined. I’ve sent the book to United States congressmen and United States senators, and I’ve heard favorable replies from them. And we’re already in our second printing of the book, just a few months after it came out, so that’s heartening. What I hope will come of this book is that we will seriously address this issue. Decency demands that even long after these events, we address them; that we teach them, that we discuss them, and that they become part of our public discourse. We need to move beyond the only thing in the California state curriculum being the sugar-cube mission model; we need to seriously investigate the history of California, its origins, and the genocide upon which it’s based.One of the things that I take away from this book, which was very difficult to write, is that there is no safe level of racism. Racism is the fundamental idea that has to be ingested in some shape or form by the killers in order to carry out mass murder, in order to carry out genocide. But genocide is too big a project to be extemporized by individuals unconnected to a state or some larger group and organizing principles. What we see in California is that the state, both state and federal officials, utilized that rhetoric of dehumanization in order to convince soldiers, militiamen, and vigilantes that what they were doing was not only proper, but was morally laudable.

And the West castigates Putin for his invasion of Ukraine! . . . Lord, have mercy!

Please click on: American Exceptionalism Indeed

Please also see my An ‘American Holocaust’ about the vast sweep of genocide committed against indigenous peoples in the Americas from their “first” discovery by Columbus in 1492.

Please also see my US Arms Business.

Footnotes:- See many of his writings here.[↩]

- See more about him and his writings here.[↩]

- See on this: The war resulted in at least 200,000 Filipino civilian deaths, mostly due to diseases such as cholera and to famine.[24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31] Some estimates for total civilian dead reach up to a million.[9] Atrocities were committed during the conflict by both sides,[32] including torture, mutilation, and executions. In retaliation for Filipino guerrilla warfare tactics, the U.S. carried out reprisals and scorched earth campaigns and forcibly relocated many civilians to concentration camps, where thousands died.[33][34][35][36][37] The war and subsequent occupation by the U.S. changed the culture of the islands, leading to the rise of Protestantism and disestablishment of the Catholic Church and the introduction of English to the islands as the primary language of government, education, business, and industry.[38]— Philippine–American War[↩]