***NOTE: Please check out the footnotes for additional, more detailed commentary. Also, there are poetry and songs in the final footnote; and four additional songs below that.***

Please also see two great sermons, one on Good Friday, the other on Easter Sunday, by my colleague Randy Klassen: both in the context of criminal/restorative justice.

Easter 2014

Breath held through long wintry snow and rain

Orchestral stage, hushed audience before first baton thrust

Shimmering dancers at every bush and tree tip

All wait.

Signal flares.

New life rises!

Concert begins.

I wrote this moments before we celebrated Easter with 19 family members.

In order to arrive at what you do not know/You must go by a way which is the way of ignorance. —T.S. Eliot in The Four Quartets

WN: While I do not get off on his style of worship, or his seeming smugness about “knowing Jesus” (seen in some other YouTube videos of his performances), Keith Green’s song here (originally composed by Annie Herring, 2nd Chapter of Acts) is top of the charts for me! Forty plus years ago, we used to listen to this often at Easter! I’m happy to “resurrect” it this Easter Season.

Speaking of resurrection: there is a person of my acquaintance who used to love this song, once at least by his account pulling over on the road to deal with overwhelming joy in response to its sheer power, an exuberance that touched him emotionally to the core. There came the day however, sadly long since, that it was all rejected, and his “Jesus” became so completely watered down that it is impossible to conjure up an understanding of why such a “Jesus” was viciously rejected and crucified–if one holds to his (un)belief. As to then rising again, Dead men simply do not rise, his “scientific” mind asserts dogmatically like the best (or worst) of any religious fundamentalist I have known.

At least as hard or more so to imagine is why a whole rabble of Jesus followers joyfully joined the ranks of martyrdom in allegiance to that belief–then or since (a rather gargantuan throng).

So is it the case, as he and some of my acquaintances now claim rather dogmatically, that the Gospels are barely “historical,” that it is simply known that scientifically, the resurrection is at best mere fairy-story, at worst a belief to be jettisoned if one time held, or rejected if considered? (I have concluded that there is no more rigid fundamentalist than one who comes to reject what once was held near and dear: in whatever field of inquiry/activity).

There is a problem with their fundamentalist pontifications: they are not qualified to make such sweeping denials–at least not as historians, not as scientists, not as theologians. They are none of them. But it’s ok with me. I bear them no ill-will for such unbelief. They are welcome to their opinions. And they can always change.

I do however demur when those (un)beliefs are pronounced as, for all intents, incontestable truths. As though if one only had intellectual/academic/moral integrity one would just know their new fundamentalism with contrary content is the only show in town . . . I do not mind that they rail against/mock certain kinds of Christian fundamentalists; that a Bishop Spong is/was their particular cup of tea. (Spong who in the books by him I read repeatedly showed himself to be one of the greatest fundamentalists of them all!) I just wish there was not the unbelief dogmatism (a variation of “religion-poisoning-everything” à la Christopher Hitchens mantra). Sigh.

Jesus throughout history has transfixed lives, making it for starters a challenge to those who deny the Gospel’s transformative power once it gets a hold of one’s life. An illustration of myriad/which is this book published in 2012, by Robert Inchausti: Subversive Orthodoxy: Outlaws, Revolutionaries, and other Christians in Disguise. Of it we read:

It may seem a surprising claim, but some of the most brilliant and original critics of modernity have been shaped by Christianity. In Subversive Orthodoxy, Robert Inchausti maps out a tradition of twentieth century thinkers-including philosophers, activists, and novelists-whose “unique contributions to secular thought derive from their Christian worldviews.” Inchausti revisits the lives and work of a stunning array of well-known Christian thinkers as well as figures not often thought of as Christian. From Walker Percy to Dorothy Day, Jacques Ellul to Marshall McLuhan, Inchausti offers a fascinating who’s who of what he calls the “orthodox avant-garde.” Subversive Orthodoxy will be an informative and encouraging read for pastors, laypeople, and students concerned about the Christian response to secular ideologies.

We read further in the Forword by Ward Mailliard:

In poetically articulate voice, [the author] amplifies the revolutionary truth that when principles of great ethical and spiritual tradition such as Christianity are ‘lived,’ they become both “subversive” and “orthodox.”

My other problem is simply: there is no historical, scientific or theological evidence that compels one to disbelieve what my acquaintance once believed and found great joy in. None on all three counts.

In this commentary, I point below to works related to issues of historical credibility of the Gospels and of “science”–a tricky term indeed, as discussed below.

There is a rough parallel between earlier “Historical Jesus Quest” historians in their dismissal of New Testament historical reliability, and earlier scientific research that to this day (scientific) materialists claim explains everything–without reference to God.

A classic text on this is by physicist Stephen M. Barr who writes:

The question before us, then, is whether the actual discoveries of science have undercut the central claims of religion, specifically the great monotheistic religions of the Bible, Judaism and Christianity, or whether those discoveries have actually, in certain important respects, damaged the credibility of materialism (Modern Physics and Ancient Faith (2003), pp. 2 & 3.)

The author, in an irenic, often understated manner, concludes the latter, saying at the end of the book:

It is certainly conceivable, if to many of us not credible, that materialism is true, but surely it is not irrational to ask for somewhat stronger arguments on its behalf (p. 256).

So with issues of historical reliability of the New Testament: it is conceivable that the documents are overall not very historically reliable. But the evidence does not compel one towards that conclusion. It is not irrational to assert that. (There is more on this below.)

When I wrote a major essay on Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (see also below) in my undergraduate German literature program, with a view to challenge Lessing’s presuppositions about the general historicity of the New Testament (“accidental truths of history” he dubbed them), and the inviolability by contrast of reason as ultimate guide to truth (“necessary truths of reason” he called them), my prof thought it rather presumptuous that I would tackle one of the Enlightenment founding notions about religion. He indicated surprise upon giving me a high mark for the paper: it was “reasonable,” he felt.

Anti-religious bias is ubiquitous in our culture, and rarely acknowledged: both product of the Enlightenment.

Reality is: the Judeo-Christian Tradition is one of the most ancient, and has throughout engaged brilliant thinkers butting up against what is known about the wider world/universe–and making sense in light of faith. Fides quaerens intellectum, was the widely-embraced 11th-century articulation by Saint Anselm, meaning: Faith seeking understanding.

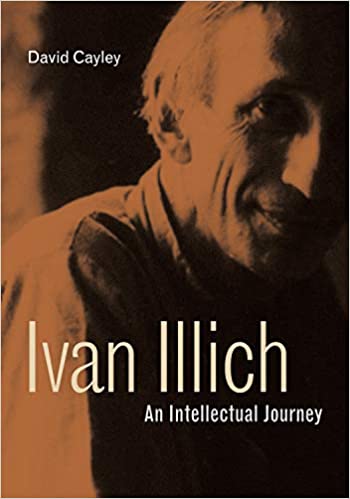

In modernity, it was claimed that “Science” displaced Faith as authoritative portal to understanding. But this is modern mythology. Noted former CBC Ideas broadcaster David Cayley highlights this in How To Think About Science, 24 hours of broadcast interviews with top historians, sociologists and philosophers of science. (Yes, I listened to them all.) One may also read his subsequent book: Ideas on the Nature of Science. Though it does not include everything from the series. The full transcript may be found on Cayley’s website, and here.

In that transcript, p. 148, during an interview with Steven Shapin (who is an historian and sociologist of science at Harvard University, co-author of Leviathan and the Air Pump, and author of A Social History of Truth and the Scientific Life), he contends that “. . . trust is imperative for constituting every kind of knowledge. Knowledge-making is always a collective enterprise: people have to know whom to trust in order to know something about the natural world.) We read:

We might mean that the idea of science has some authority, that people think that science has got a method that guarantees the production of reliable knowledge, and that’s an intriguing idea, except the evidence is that not just lay people, but scientists themselves, have tremendous disagreements about what it is that method–the scientific method–might be. So we’re left with rather a puzzle about what we might mean by saying science is the characteristic culture of modernity, and I’d like to leave it at that because I’d like to encourage a lot more interest in the conditions under which we can talk about science and the modern world.

Religion, we should understand now, has enormous authority. Whether or not it’s increasing its authority in our public life, especially in this country [the USA], is another matter. But religion did not go away. Religion was not killed by science. For all that the commentators at the end of the 19th century or early 20th century said so, they were wrong. Religion is alive and well.

The Wikipedia article states about Stephen Barr’s book adduced above:

Modern Physics and Ancient Faith (2003) is a book by Stephen M. Barr, a physicist from the University of Delaware[1] and frequent contributor to First Things. This book is “an extended attack” on what Barr calls scientific materialism. National Review says of the book: “[A] lucid and engaging survey of modern physics and its relation to religious belief. . . . Barr has produced a stunning tour de force . . . [a] scientific and philosophical breakthrough.”[2]

And further:

The book is divided into five parts spanning 26 chapters. The main religious and philosophical themes include determinism, mind as a machine, anthropic principle, and the big bang theory.[3] Its main thesis is that science and religion only appear in conflict because many have “conflated science with philosophical materialism.”

. . . except the evidence is that not just lay people, but scientists themselves, have tremendous disagreements about what it is that method–the scientific method–might be.

Another outstanding book in relation to quantum theory, but along Girardian thought-lines, is: Reflection in the Waves: The Interdividual Observer in a Quantum Mechanical World (Breakthroughs in Mimetic Theory), by Pablo Bandera. Of it one reads:

The incredible success of quantum theory as a mathematical model makes it especially frustrating that we cannot agree on a plausible philosophical or metaphysical description of it. Some philosophers of science have noticed certain parallels between quantum theory and the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas, and these parallels are deepened and strengthened if the “observer” of modern physics is associated with the “intellect” of scholastic ontology. In this case we are talking about a human observer. But this type of observer has a unique quality that is not considered at all by either physics or scholastic philosophy—the human observer is mimetic and therefore “interdividual.” By taking this fundamental anthropological fact into account, it turns out that the critical gaps still separating Aquinas from modern physicists can be effectively closed, reconciling the realism of Aquinas with the empirical evidence of quantum mechanics. This book explores this new bridge between the physical and the human—a bridge essentially designed by scholastic theory, clarified by mimetic theory, and built by quantum theory—and the path it opens to that metaphysical understanding for which philosophers of modern science have been striving. It is an understanding, not merely of the physical but of physics in the fuller sense of what is real and what is true. Here the reader will find a physics that describes the natural world and our place as mimetic observers within it.

Near the end, the author writes:

But while we have learned to trust nature, the more modern among us still seem to distrust the sacred as much as the ancients did. Every ancient sacred ritual was an attempt to avoid, appease, or control the sacred, and every modern appeal to a purely physical or mechanistic “objectivity” is essentially the same. Our ancestors turned from the sacred in fear and trembling, and we moderns turn away in haughty disdain. But we turn away just the same (p. 194)

He finishes with this:

More specifically, the difference between modern science and religion, between the study of the objectively real world and the study of the divinely created world, is the difference between the world as defined by the observer’s human models and the world as defined by an observer’s divine model. In other words, the line between science and religion is the line between objective reality and divine truth. The physicist is justified in claiming that his field deals with what is real and observable, but he must ultimately look to God to know if his observations are true. This is, after all, what every scientist of good conscience knows intuitively, regardless of his or her specific understanding of God. And it is the solid intuition of these good people that allows science to progress, faithfully, in the right direction.

I’m quite at a loss as to what to do with such overwhelming prejudice and closed-mindedness as adduced above with such underwhelming historical evidence.

Nonetheless, before continuing, it is worth airing dirty laundry first, by quoting top Irish literary critic Terry Eagleton, that:

Religion has wrought untold misery in human affairs. For the most part, it has been a squalid tale of bigotry, superstition, wishful thinking, and oppressive ideology (Reason, Faith, and Revolution: Reflections on the God Debate, Terry Eagleton, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009, p. xi). My (long) interactive book review is here.)

If one disputes this (well, maybe legitimately “for the most part”)1, one is not a good student of history.

One of the best counter-narrative sweeping studies is by Sir Larry Allan Siedentop, an American-born British political philosopher with a special interest in 19th-century French liberalism. The book’s title is: Inventing the Individual: The Origins Of Western Liberalism.

A reviewer, Nicholas Lezard, writes:

Like many, I had assumed that notions of individual liberty didn’t come into play until the latter end of the Enlightenment. It was something to do with Voltaire, perhaps, or the second sentence of the American Declaration of Independence. If the Church had anything to do with individuality, it was as a brake on it, or a countermeasure. We were all just anonymous units before the power of God.

Siedentop demonstrates that the picture is much more complex. In fact, he claims, it is Christianity we have to thank, and particularly the Christianity that was being formed in the dark and early medieval ages, for our concept of ourselves as free agents. He starts in ancient Greece and Rome: there, the faculty of reason was only to be found in the ruling elite, which, in effect, meant men of a certain class in a city state. If you were a woman, merchant, or slave, all you could really use your brains for were, respectively, gossip, mercantile calculation, and unthinking obedience. (A glance at newsagents’ shelves these days may make you suspect that civilisation has gone retrograde in these respects, but let us pass on that for the moment.) Even philosophers, who had no direct allegiance to a specific place, were for a while suspect. However, seeds were sown, and things got interesting when Greek- and Latin-speaking urban dwellers around the Mediterranean started encountering the Jewish diaspora:

“Just what was it that, rather suddenly, made Jewish beliefs so interesting? It was partly a matter of imagery. The image of a single, remote and inscrutable God dispensing his laws to a whole people corresponded to the experience of peoples who were being subjugated to the Roman imperium.”

This is the beginning of a thoughtful jaunt through several centuries of developing theological and legal thinking. The stars are Augustine, Duns Scotus and William of Ockham: he of the famous Razor, the injunction that “it is futile to work with more entities when it is possible to work with fewer”. (Here, the entities concerned were demons, but the principle “a plurality must not be asserted without necessity” came to be quickly understood as very much more widely applicable.)

This is not a book to take on a beach holiday; it is chewy, involved stuff, and if at times it looks as though Siedentop is repeating himself, you may well be grateful, as I was, because you might not have got it first time round. I have never hitherto had to think about, for example, medieval corporation law and its relation to ecclesiastical authority. But the book is, once you get past the superficial difficulties, not too hard to grasp, and its basic principle – “that the Christian conception of God provided the foundation for what became an unprecedented form of human society” – is, when you think about it, mind-bending.

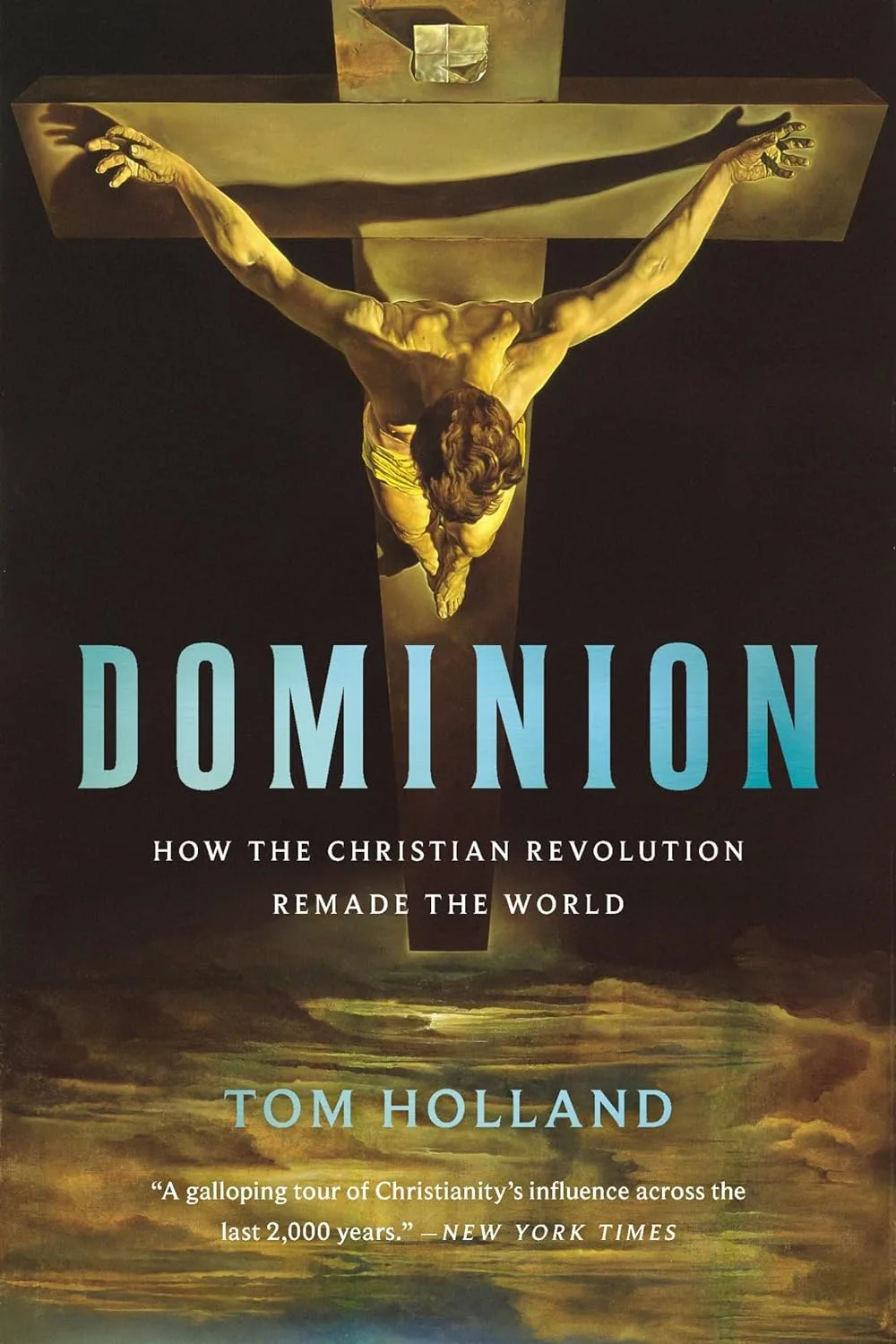

There is another book I highly recommend: .

Of it, we read in Wikipedia:

The book is a broad history of the influence of Christianity on the world, focusing on its impact on morality – from its beginnings to the modern day.[1] According to the author, the book “isn’t a history of Christianity” but “a history of what’s been revolutionary and transformative about Christianity: about how Christianity has transformed not just the West, but the entire world.”[2]

Holland contends that Western morality, values and social norms ultimately are products of Christianity,[1][3][4] stating “in a West that is often doubtful of religion’s claims, so many of its instincts remain — for good and ill — thoroughly Christian”.[5] Holland further argues that concepts now usually considered non-religious or universal, such as secularism, liberalism, science, socialism and Marxism, revolution, feminism, and even homosexuality, “are deeply rooted in a Christian seedbed,”[6][7][8] and that the influence of Christianity on Western civilization has been so complete “that it has come to be hidden from view”.[1][7]

It was released to positive reviews, although some historians and philosophers objected to some of Holland’s conclusions.

Background

Tom Holland has previously written several historical studies on Rome, Greece, Persia and Islam, including Rubicon, Persian Fire, and In the Shadow of the Sword.[9] According to Holland, over the course of writing about the “apex predators” of the ancient world, particularly the Romans, “I came to feel they were increasingly alien, increasingly frightening to me”.[10] “The values of Leonidas, whose people had practised a peculiarly murderous form of eugenics and trained their young to kill uppity Untermenschen by night, were nothing that I recognised as my own; nor were those of Caesar, who was reported to have killed a million Gauls, and enslaved a million more.”[1] This led him to investigate the process of change leading to today, concluding “in almost every way, what makes us distinctive today reflects the influence over two thousand years of the Christian story.”[10] (Emphasis added)

Prefiguring the book, in 2016 Holland penned an essay in the New Statesman describing how he was “wrong about Christianity,”[11][12] titled: “Why I was wrong about Christianity: It took me a long time to realise my morals are not Greek or Roman, but thoroughly, and proudly, Christian.” We read:

By the time I came to read Edward Gibbon and the other great writers of the Enlightenment, I was more than ready to accept their interpretation of history: that the triumph of Christianity had ushered in an “age of superstition and credulity”, and that modernity was founded on the dusting down of long-forgotten classical values. . . “Thou hast conquered, O pale Galilean,” Swinburne wrote, echoing the apocryphal lament of Julian the Apostate, the last pagan emperor of Rome. “The world has grown grey from thy breath.” Instinctively, I agreed.

…

The longer I spent immersed in the study of classical antiquity, the more alien and unsettling I came to find it.

. . . It was not just the extremes of callousness that I came to find shocking, but the lack of a sense that the poor or the weak might have any intrinsic value. As such, the founding conviction of the Enlightenment – that it owed nothing to the faith into which most of its greatest figures had been born – increasingly came to seem to me unsustainable.

“We preach Christ crucified,” St Paul declared, “unto the Jews a stumbling block, and unto the Greeks foolishness.” He was right. Nothing could have run more counter to the most profoundly-held assumptions of Paul’s contemporaries – Jews, or Greeks, or Romans. The notion that a god might have suffered torture and death on a cross was so shocking as to appear repulsive. Familiarity with the biblical narrative of the Crucifixion has dulled our sense of just how completely novel a deity Christ was. In the ancient world, it was the role of gods who laid claim to ruling the universe to uphold its order by inflicting punishment – not to suffer it themselves. (Emphasis added)

. . . the claim that “religion is … essentially prone to violence is one of the foundational legitimating myths of the liberal nation-state. . . It is this claim that I find both unsustainable and dangerous. – William Cavanaugh

“Every sensible man,” Voltaire wrote, “every honourable man, must hold the Christian sect in horror.”2

Even Voltaire might have been critiqued by my in-laws for his failure to use inclusive language!. . . — not knowing their political correctness is (by me generally welcome) product of Christian ethics.

Holland writes in direct response:

As such, the founding conviction of the Enlightenment – that it owed nothing to the faith into which most of its greatest figures had been born – increasingly came to seem to me unsustainable. (Emphasis added)

One must quietly, respectfully but surely ask:

Who are the dogmatic “fundamentalists” here, proverbial heads resolutely stuck in the sands of historical/historiographical ignorance–from Voltaire to neoatheists to my relatives, acquaintances, and a vast throng of post-Enlightenment (sometimes wilful3) dupes?

Another philosopher-historian, William Cavanaugh, in The Myth of Religious Violence: Secular Ideology and the Roots of Modern Conflict, counters our ubiquitous Western notion that “religion” (Christianity) historically, and in resurgent worldwide Islam, is indisputably, mainly, violent. Cavanaugh asserts on the contrary that the claim that “religion is … essentially prone to violence is one of the foundational legitimating myths of the liberal nation-state (p. 4).”

Conventional wisdom implies that “religions” such as Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Judaism over against “ideologies and institutions” such as nationalism, Marxism, capitalism, and liberalism, are “essentially more prone to violence – more absolutist, divisive, and irrational – than the latter.” In response, the author is blunt: “It is this claim that I find both unsustainable and dangerous (p. 6, emphasis added).” “Violence” in relation to those cited in the book “generally means injurious or lethal harm and is almost always discussed in the context of physical violence, such as war and terrorism (p. 7).”

Not only does the author use the term “myth” to indicate the claim is false, “but to give a sense of the power of the claim in Western societies (p. 6).”4 The claim seems a given and inevitable – and therefore difficult to refute. (From my Book Review of the above book and another by Cavanaugh. You may also listen to him interviewed by David Cayley, in a series titled: After Atheism: New Perspectives on God and Religion. It was designed initially as a 12-part series, the second set of interviews entitled The Myth of the Secular. The listener is in for a veritable feast of ideas spanning a 30-plus year career of programs produced for CBC Ideas by David Cayley. The two programs just mentioned were David Cayley’s last offerings before retirement. Do see his superb website by clicking on his highlighted name. There is much written material as well.)

Again, I have relatives who are so fundamentalist (read dogmatic) about their dearly held embrace of said Enlightenment mythology, that there is no way in to even engage them with such a thoroughly researched and documented set of theses as noted in the two books above. Sadly, one is at a loss about what to do with such blind prejudice other than allow those so self-duped to simply stew in the juices of their uninformed biases. Quidquid recipitur, ad modum recipientis recipitur. The recipient must be at least open to possible attunement with the message, or miss it altogether! In their cases, they have jettisoned an earlier religious fundamentalism only to display Phoenix-like its quintessential spirit in virulent, even arrogant anti-Christian sentiment.

The above highlights a more general problem with the recent spate of neoatheistic writings. Renowned Irish literary critic Terry Eagleton engages such obstinate — even silly — dogmatism in Reason, Faith and Revolution: Reflections on the God Debate. My interaction with the book may be found by clicking on the title. Another pertinent article by John Mark N. Reynolds is: “The Five Worst “Arguments” (or Claims) Made by Internet Atheists.”

For more on this, please view the following quotes:

Assumptions that I had grown up with—about how a society should properly be organised, and the principles that it should uphold—were not bred of classical antiquity, still less of ‘human nature’, but very distinctively of that civilisation’s Christian past. So profound has been the impact of Christianity on the development of Western civilisation that it has come to be hidden from view. It is the incomplete revolutions which are remembered; the fate of those which triumph is to be taken for granted.—Tom Holland in Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World, pp.16 & 17.

The relationship of Christianity to the world that gave birth to it is, then, paradoxical. The faith is at once the most enduring legacy of classical antiquity, and the index of its utter transformation. . . It has long survived the collapse of the empire from which it first emerged, to become, in the words of one Jewish scholar, ‘the most powerful of hegemonic cultural systems in the history of the world’ (A Radical Jew: Paul and the Politics of Identity, Daniel Boyarin, p. 9.)—Tom Holland in Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World, pp. 10 & 11.

Christianity’s principles . . . continue to dominate much of the world; Tom Holland’s thoughtful, astute account describes how and why . . . An insightful argument that Christian ethics, even when ignored, are the norm worldwide.—Kirkus (starred review)

When we condemn the moral obscenities committed in the name of Christ, it is hard to do so without implicitly invoking his own teaching.—Irish literary critic Terry Eagleton in: Dominion by Tom Holland, review – the legacy of Christianity

Modern reformers complain, quite justly, about the violence of Christianity, René Girard says, but they fail to notice that “they can complain [only] because they have Christianity to complain with.”—David Cayley in Ivan Illich: An Intellectual Journey, p. 404.

A little learning is a dang’rous thing.—Alexander Pope

Please also see, by , December 24, 2019, Christmas Turns the World Upside Down: What does it mean for God’s power to be “made perfect in weakness”?

It’s Hard to Believe

I think there is no suffering greater than what is caused by the doubts of those who want to believe. I know what torment this is, but I can only see it, in myself anyway, as the process by which faith is deepened. A faith that just accepts is a child’s faith and all right for children, but eventually you have to grow religiously as every other way, though some never do. What people don’t realize is how much religion costs. They think faith is a big electric blanket, when of course it is the cross. It is much harder to believe than not to believe. If you feel you can’t believe, you must at least do this: keep an open mind. Keep it open toward faith, keep wanting it, keep asking for it, and leave the rest to God. — Flannery O’Connor in The Habit of Being: Letters of Flannery O’Connor

The ethical tools by which they critique Christianity are provided to Western culture in the first place by the revolutionary moral eruption of Christian faith in the first century: over against Ancient Greek and Roman cultures, both awash in fundamental inequality and denial of human rights–except for the elite male minorities. This as said is starkly seen in Sir Larry Siedentop’s brilliant study, Inventing the Individual: The Origins of Western Liberalism.

The profound ignorance out of which they critique Christianity is therefore a great irony: one widely displayed amongst Christianity’s self-congratulatory “cultured despisers.” (See: On Religion: Speeches to its Cultured Despisers (1799).)

My wife and I however long since gratefully committed lèse-majesté and self-expulsion from that sorry realm of facile, faux deontological unbelief. Well, we really never were inhabitants (though we likewise abandoned an earlier Christian fundamentalism. (For insight, though

from the (but-not-unlike) American side, see my review of Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation . . .)

David Cayley puts it thus:

But the Enlightenment and its sequels say that Christianity is not Christian enough, just as the Reformation had said that Catholicism had not been Christian enough. Modern reformers complain, quite justly, about the violence of Christianity, Girard says, but they fail to notice that “they can complain [only] because they have Christianity to complain with.” In this way, there arises a race of super-Christians who have renounced Christianity but have no other basis for their fantastic hopes and their extreme sensitivity to injustice than the Gospel that they consider to be entirely superseded. This creates an extremely confusing situation, in which what Illich considers obvious, and is obvious from his point of view, is far from obvious to those who take their own good will for granted and believe themselves to be the authors of their own “values.” (Ivan Illich: An Intellectual Journey, p. 404. Emphasis added. See also the post of our discussion of this book:

Sigh: the acquaintance and his wife of whom I write are amazingly unaware of their own ethical epistemological delusions.

Of course, my acquaintance is welcome to his (un)beliefs! No I don’t believe he is going to hell for rejecting the Christian faith of his previous self. But I have not heard him express for many a year the kind of high-spirited joy he once had in the resurrection–and with it the whole bag of for him once life-giving tricks.

We receive the Spirit of truth so that we can know the things of God. In order to grasp this, consider how useless the faculties of the human body would become if they were denied their exercise. Our eyes cannot fulfil their task without light, either natural or artificial; our ears cannot react without sound vibrations, and in the absence of any odour our nostrils are ignorant of their function. Not that these senses would lose their own nature if they were not used; rather, they demand objects of experience in order to function. It is the same with the human soul. Unless it absorbs the gift of the Spirit through faith, the mind has the ability to know God but lacks the light necessary for that knowledge.—From the treatise on the Trinity by Saint Hilary of Poitiers

I find it sad . . . about my friend’s unbelief — for him and his wife. (Not that what I believe is “certainty” either. It is after all “faith”—that ever is only gift. And it does bring great joy!)

For those however who might be on the contrary more open-minded, I’ll point you presently to (if unaware) some of the historical/scientific scholarship that influences me–if as well you are considering these things. In light of Dr. Shapin’s statement above about trusting these various voices: I do.

Paradoxically though, there are myriad who have come to the Christian faith entirely outside of any (or alongside a) “rational” path. These are the Christian mystics who have left a legacy of profound encounters with God for us to learn from; to delight in, in our faith journeys. They belong to every age.

One such is classicist, “anthropologist of everyday life,” researcher, broadcaster, filmmaker, award-winning author, and delightfully enthusiastic about wherever she directs her brilliant mind, Margaret Visser. She is a deeply committed Christian, who came to faith through a mystical experience in a gym exercise class at the University of Toronto.5

Now for some of my influences:

Jesus Remembered: Christianity in the Making, Volume 1, James D. G. Dunn, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003. The two other volumes are:Beginning from Jerusalem (Volume 2, 2009) and Neither Jew nor Greek: A Contested Identity (Volume 3, 2015). Together, the three volumes add up to 3,312 pages, including vast bibliographies and footnotes! This besides massive works by the same author on Jesus and Paul. A sampling of others: The Theology of Paul the Apostle (2006); The New Perspective on Paul (2007); a collection of earlier essays, Jesus, Paul, and the Gospels (2011); his collection of essays on The Oral Gospel Tradition (2016); Jesus According to the New Testament (2019); and he has authored other books, commentaries and innumerable articles contributing to a wide assortment of scholarly works in his field. Sadly, Dr. Dunn died at the age of 80 in 2020. There had been no more top-notch and prolific Early Church historian writing today! On the resurrection, Dunn avers:

Jesus Remembered: Christianity in the Making, Volume 1, James D. G. Dunn, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003. The two other volumes are:Beginning from Jerusalem (Volume 2, 2009) and Neither Jew nor Greek: A Contested Identity (Volume 3, 2015). Together, the three volumes add up to 3,312 pages, including vast bibliographies and footnotes! This besides massive works by the same author on Jesus and Paul. A sampling of others: The Theology of Paul the Apostle (2006); The New Perspective on Paul (2007); a collection of earlier essays, Jesus, Paul, and the Gospels (2011); his collection of essays on The Oral Gospel Tradition (2016); Jesus According to the New Testament (2019); and he has authored other books, commentaries and innumerable articles contributing to a wide assortment of scholarly works in his field. Sadly, Dr. Dunn died at the age of 80 in 2020. There had been no more top-notch and prolific Early Church historian writing today! On the resurrection, Dunn avers:

As a historical statement we can say quite firmly: no Christianity without the resurrection of Jesus. As Jesus is the single greatest ‘presupposition’ of Christianity, so also is the resurrection of Jesus. To stop short of the resurrection would have been to stop short (p. 826).

By stark contrast, I once listened for 4½ hours or so to my acquaintance mentioned above as he trashed the Gospels as unhistorical and hence quite dismissible–in his loquacious rendition of a virulent anti-creed. Perhaps ( 😉 ) one can guess whom I find more credible: the three historians mentioned above and below (and so many more!)–over against the profound, comparatively (though “comparison” is not even a register in his case) uninformed bias of my acquaintance . . .

Another top-notch Early Church historian, N. T. Wright, published Volume III of his “Christian Origins and the Question of God” series with the title: The Resurrection of the Son of God. Wright asserts:

Another top-notch Early Church historian, N. T. Wright, published Volume III of his “Christian Origins and the Question of God” series with the title: The Resurrection of the Son of God. Wright asserts:

The fact that dead people do not ordinarily rise is itself part of early Christian belief, not an objection to it. The early Christians insisted that what had happened to Jesus was precisely something new; was, indeed, the start of a whole new mode of existence, a new creation. The fact that Jesus’ resurrection was, and remains, without analogy is not an objection to the early Christian claim. It is part of the claim itself (p. 762).6

A world-renowned journalist/historian with prodigious output is Paul Johnson. An octogenarian when he wrote Jesus: A Biography from a Believer, he invites readers to request any substantiating scholarship–readily available from him–for his biography of Jesus. (For those who object that he is clearly biased in light of the subtitle, the very objection of course carries its own objection of bias in turn!) Johnson writes at the end of the book:

A world-renowned journalist/historian with prodigious output is Paul Johnson. An octogenarian when he wrote Jesus: A Biography from a Believer, he invites readers to request any substantiating scholarship–readily available from him–for his biography of Jesus. (For those who object that he is clearly biased in light of the subtitle, the very objection of course carries its own objection of bias in turn!) Johnson writes at the end of the book:

The Gospels are designed to be read and reread. The oftener we do so, the greater our delight in them, the deeper our understanding, and the more we grasp their realism. They are the truth. What they tell us actually happened. The characters are real. The details are strangely, sometimes mysteriously, convincing. As we go on reading, the many centuries which intervene gradually slip away, and we become familiar with a world not so different from our own . . . [The Gospels’] message, at its simplest, is do as Jesus did. That is why his biography, in our terrifying twenty-first century, is so important. We must study it, and learn (pp. 224 – 226).7

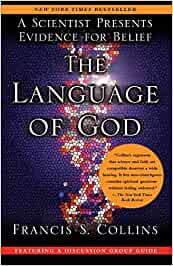

Francis Sellers Collins is an American physician-geneticist noted for his discoveries of disease genes and his leadership of the Human Genome Project. He is director of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, United States. He is a scientist’s scientist in ways that again put my acquaintance into a totally different league, so bush as not even to bear comparative mention. Please see this article of Collins’ receiving the 2020 Templeton Prize–in the context of COVID-19 and anti-Science Trump: NIH Chief, BioLogos Founder Francis Collins Wins Templeton Prize. Then please see A Long Talk With Anthony Fauci’s Boss About the Pandemic, Vaccines, and Faith. Dr. Collins expresses succinctly why he came to and remains in the Christian faith out of an earlier atheism. Collins has published several books in relation to his Christian faith. In The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief (incidentally, University of British Columbia’s President and Vice Chancellor Santa J. Ono states that this is his favourite book), Dr. Collins writes in the Introduction:

Francis Sellers Collins is an American physician-geneticist noted for his discoveries of disease genes and his leadership of the Human Genome Project. He is director of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, United States. He is a scientist’s scientist in ways that again put my acquaintance into a totally different league, so bush as not even to bear comparative mention. Please see this article of Collins’ receiving the 2020 Templeton Prize–in the context of COVID-19 and anti-Science Trump: NIH Chief, BioLogos Founder Francis Collins Wins Templeton Prize. Then please see A Long Talk With Anthony Fauci’s Boss About the Pandemic, Vaccines, and Faith. Dr. Collins expresses succinctly why he came to and remains in the Christian faith out of an earlier atheism. Collins has published several books in relation to his Christian faith. In The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief (incidentally, University of British Columbia’s President and Vice Chancellor Santa J. Ono states that this is his favourite book), Dr. Collins writes in the Introduction:

So here is the central question of this book: In this modern era of cosmology, evolution, and the human genome, is there still the possibility of a richly satisfying harmony between the scientific and spiritual worldviews? I answer with a resounding yes! (pp. 5 & 6)8

The Gift of Faith

Faith is what you have in the absence of knowledge. . . and that absence doesn’t bother me because I have got, over the years, a sense of the immense sweep of creation, of the evolutionary process in everything, of how incomprehensible God must necessarily be to be the God of heaven and earth. You can’t fit the Almighty into your intellectual categories. If you want your faith, you have to work for it. It is a gift, but for very few is it a gift given without any demand for time devoted to its cultivation. . . Even in the life of a Christian, faith rises and falls like the tides of an invisible sea. It’s there, even when one can’t see it or feel it, if one wants it to be there.—Flannery O’Connor in Cries from the Heart.

We read:

While a medical student at the University of North Carolina, Collins saw religion comfort patients in physical and existential pain. When an elderly woman with an incurable heart condition asked him what he believed, he found himself at a loss. With time, the question began to feel overwhelming, urgent, and unavoidable. Even as Collins held on to the idea that science could untangle the mechanics of life, he read C. S. Lewis and consulted his first wife’s pastor. Eventually, he came to the conclusion that faith, more than science, could help illuminate morality and existence. One day, while hiking in the Cascades, he saw a waterfall frozen in three parts and took it as a sign of the Holy Trinity. In the decades that followed, he argued that science and religion could exist alongside each other. In 2006, he published “The Language of God,” a best-selling book that presents evidence that, in his view, justifies faith. In it, Collins argues that faith is rational, that it can help answer life’s deepest questions, and that the challenges of the twenty-first century require a harmony between science and religion, not just a ceasefire. He then founded BioLogos, an organization that supports the view that God created all things through the instrument of evolution.

In July, 2009, President Barack Obama nominated Collins to lead the National Institutes of Health, the largest supporter of biomedical-research in the world. Collins was by then a renowned geneticist who had helped to discover key genes behind cystic fibrosis, Type 2 diabetes, Huntington’s disease, neurofibromatosis, and other conditions. Still, he faced high-profile opposition from within the scientific community. The prominent Harvard cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker, who has been an outspoken proponent of atheism, called Collins “an advocate of profoundly anti-scientific beliefs.” In an Op-Ed in the Times, the public intellectual Sam Harris, another prominent atheist, argued that “few things make thinking like a scientist more difficult than religion,” and expressed concern that Collins’s views would undermine efforts to understand the human mind. “One can only hope that these convictions will not affect his judgment at the institutes of health,” Harris wrote. The U.S. Senate appeared not to share these concerns: it confirmed him with a unanimous vote.

One might add: So much for vaunted atheistic religious/ideological tolerance; so much for atheistic anti-belief dogmatism . . . For a brilliant, mischievous take-down of the belief system of atheism, please see my book review of: Reason, Faith and Revolution: Reflections on the God Debate, by renowned Irish literary critic, Terry Eagleton. I write:

I had generally felt uninterested in the recent spate of neoatheistic publications, including The God Delusion by Richard Dawkins, and God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything, by Christopher Hitchens. Both books and the “God Debate” are the focus of the book under discussion. In 2010, Eagleton, a noted literary critic and theoretical Marxist, gave the most prestigious series of theological lectures in English today: The Gifford Lectures, at the University of Edinburgh.9

That lecture series continued his probing this theme. With Eagleton’s offering, I suddenly realized how vital to our very humanity this discussion is! What, if after all, both the dilemma of the human condition and its solution cut far more deeply than the best offerings of secular good works done by say the International Red Cross, the Canadian International Development Agency, or the American Peace Corps?10

What if, after all, most of the Christian West with its early inversion of the Cross into ultimate symbol of violence, the Sword, was massively unfaithful to humanity’s ultimate destiny of peace that Judeo-Christian Scripture knows as the Kingdom of God? This publication raises these issues exquisitely and much more.

Eagleton playfully amalgamates the above atheistic authors under the signifier “Ditchkins,” so alike, and so incredibly ignorant (in the strict sense of meaning “not knowing”) are the two authors about their subject matter. The book itself is based on Reason, Faith, and Revolution – Eagleton, Terry Lectures series: given by Eagleton in 2009 at Yale University.

I have similarly generally felt uninterested in more than a century of “Historical Jesus Quest Studies,” and usually put issues of atheism and New Testament revisionism together–over against hermeneutical revisionism of the Bible. New Testament theologian Luke Timothy Johnson says of Historical Jesus Questers generally:

Perhaps after all these authors have not escaped the tendencies so acutely described by [Albert] Schweitzer. Does not [one such author’s] picture of a peasant cynic preaching inclusiveness and equality fit perfectly the idealized ethos of the late twentieth-century academic (quoted in Richard Hays’ The Moral Vision of the New Testament: Community, Cross, New Creation – A Contemporary Introduction to New Testament Ethics, p. 167)?

It seems that both kinds of naysayers too often trade in arrogance and disdain towards the traditionally “faithful.” The naysayers also seem to aver we’d all be much better off if we or “God” or Jesus were made in their image: “liberal dogmatists, doctrinaire flag-wavers for Progress, and Islamophobic intellectuals (p. 169),” or early twenty-first century (mainly) white male academic ultimately “enlightened” Historical Jesus Questers. C.S. Lewis wrote decades ago ruefully that there is regularly a fresh crop of publications every fall of such tiresome revisions. This appears to be still the case.

In the face of the above scholarly testimonials, I find my acquaintance’s dogmatic fundamentalist unbelief wears a bit thin . . .

Again: mine is not a contrary dogmatic fundamentalist belief critique/affirmation. Rather, to cite Professor Barr’s words yet again, slightly paraphrased:

It is certainly conceivable, if to many of us not credible, that [my acquaintance’s inverse fundamentalism] is true, but surely it is not irrational to ask for somewhat stronger arguments on its behalf.

Hope you too can thrill to the joy of the resurrection! If you can, I hope the above song and reflections will contribute to it!11

In that joyful affirmation, you may take to heart then act on Bishop Thomas Gumbleton’s challenge to us in his Easter Sunday 2019 homily: “Have complete faith in the Resurrection.”

Then take in this joyful Easter rendition of Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah:

The phrase “. . . save us from ourselves” is used in the song above. The following video, a beautiful plaintive cry of the heart written and sung by Dee Wilson in the context of the huge Black Lives Matter summer protests of 2020, and against the backdrop of the pandemic, also uses that phrase and explains why we all stand in need of that kind of salvation . . .

OK: One more hugely hopeful Easter Song!–from Good Shepherd Music Collective:

Please also see this: FreerangeFriday: The Easter Cup of What’s Next, April 5, 2024, by Lilly Lewin, that includes a joyful Easter Song by Matt Maher. In it:

We who follow Jesus know in our hearts that we are Easter People, people of the resurrection, people who are called to live out a new way of love and justice in our neighborhoods and in the world. We know these things in our hearts, but the stuff of life too often gets in the way of actually living it out.

How have we forgotten that it’s still Easter? This week after the Resurrection have we lost sight of the power of Holy Week? Have we already moved on to the next thing and lost sight of the celebration? Are we still in the Upper Room waiting for what’s next? Or are we more like Thomas, out and about doing the next things and needing more proof?

Too often we forget that Easter is a season of the church year, not just one day! It’s Eastertide!

Eastertide: “Traditionally lasting 40 days to commemorate the time the resurrected Jesus remained on earth before his Ascension, in some western churches Eastertide lasts 50 days to conclude on the day of Pentecost or Whitsunday.” Wikipedia

He is risen! He is risen indeed! Amen.

Footnotes:- “Maybe”?! In fact, it can and has been vigorously challenged in the case of historic Christianity. Please read on.[↩]

- L’examen important de Milord Bolingbroke. Ecrit sur la fin de 1736.[↩]

- David Cayley writes:

Modern reformers complain, quite justly, about the violence of Christianity, [René] Girard says, but they fail to notice that “they can complain [only] because they have Christianity to complain with.” In this way, there arises a race of super-Christians who have renounced Christianity but have no other basis for their fantastic hopes and their extreme sensitivity to injustice than the Gospel that they consider to be entirely superseded. – Ivan Illich: An Intellectual Journey, p. 404.

See also further below. It is such an irony in the West — and by extension worldwide — that one’s ethical epistemology is profoundly Christian, product of the moral upheaval of the first-century Christian revolution, yet unacknowledged and railed against: quite exactly (slight variation) “cutting off the nose to spite the faith”. . .[↩]

- Voltaire — as seen above –a principal myth-maker[↩]

- She speaks of it in a documentary called The Geometry of Love. (The book by the same title is an amazing read.) You can also hear various pieces of interviews with her on a CBC retrospective. You’re in for a treat! I also reviewed her The Gift of Thanks: The Roots, Persistence, and Paradoxical Meanings of a Social Ritual (another treat), along with two others on gratitude (Toronto: HarperCollins, 2010, (p. 712).)

She gives no indication that any of the foregoing was at play at all in her conversion.

So to be clear: I make no assertion that what is offered compels belief–or “demands a verdict” as a pseudo-intellectual Christian apologist contends. I only claim it is not irrational to ask for somewhat stronger arguments on my acquaintance’s (un)beliefs’ behalf.Through God’s grace, our minds can explore, understand, and reflect on creation and even on God’s own works, but we can’t think our way to God. That’s why I’m willing to abandon everything I know, to love the one I cannot think. He can be loved, but not thought.—The Cloud of Unknowing

God from experience and what otherwise I can tell does not force anything on anyone! God is the great Cosmic Wooer not a Crusader . . . Therefore, how dare I in matters of faith presume to impose anything on anyone?! Faith is always only a gift.

Brilliant 20th-century social critic and Catholic priest Ivan Illich, according to David Cayley, asserted that:

“Faith … cannot be the foundation for an ethical imperative” because faith “is either there or not there”—it is a gift which cannot be presupposed or in any way commanded or required. He sought rather an “ethical awakening” and tried to stimulate it by showing that true freedom is only possible within limits. (Ivan Illich: An Intellectual Journey, Penn State University Press, p. 153; emphasis added).

There of course are (am I bending over backwards here?) valid personal reasons people leave/fail to embrace Christian faith. How dare anyone dispute/critique that? Some have been deeply hurt/traumatized by the Church, by us Christians . . .

I am moved by this reflection from Lore Wilbert: “Judas, with the piece of bread.”:How few things there are which can be proved! Proofs only convince the mind. Who has ever been able to prove that tomorrow will come, and that we shall die? And what could be more generally believed?… In short, we must rely on faith when the mind has once perceived where truth lies, in order to quench our thirst and color our minds with a faith that eludes us at every moment of the day.—Blaise Pascal; Source: A Third Testament

It seems like every week another friend or acquaintance is saying they’ve found Christianity wanting. It’s not always Christ they find wanting, but his followers. Russell Moore wrote a strong and stirring piece this past week on why this might be, and I recommend you read it.

But this morning as I read John 13, I took a lot of comfort in this line, that Judas, whether he ate the bread or not, still brought it with him.

We have the opportunity to respond in a few ways when friends struggle or leave Christianity. We can write scathing prayers couched in sneering judgment, we can pity them and let them know how wrong they’ve got it. Or we can look to Jesus who offered bread and wine to the one who would reject him, who let him eat or take it with him, who didn’t call him out by name in public, but who let the scene play all the way out.

…

Who knows how many times our friends have received communion, their faith wobbly and the sins done against them and their own sin at the forefront of their minds? But they still took it then and brought it with them when they left.

That comforts me this morning because I believe Christ cares about the one. I believe Christ came to save all. And I believe all have eternity written within them, and some carry it with them as they go. And perhaps someday when they need it, they will find the bread, the body, just as available to them then as it was when they left.

I can only add: Amen.

Further: I subscribe to Christoph Friedrich Blumhardt‘s (an amazing 19th-century theologian) affirmation: Everyone Belongs to God: Discovering the Hidden Christ. So I can leave all that (thank God!) to God.

My more modest contention is simply: what follows in point form (for me!) precludes any facile unbelief on points of history or science.((The Easter 2019 article (“The ‘literal flesh-and-blood’ resurrection is the heart of my faith”) by James Martin, S.J. captures the essence. The reader may weigh it.

In it we read:

Let me offer my own perspective on this. I believe that Jesus Christ rose from the dead on the first Easter Sunday. And I do not see that as any sort of parable or metaphor. This is, frankly, the very heart of my faith.

Also, I do not believe that we can or should reduce the great mystery of the resurrection to an experience that occurred within the community. This is what some contemporary theologians have posited: that Christ “rose” within the community.

Theological approaches differ, but, in essence, some theologians offer the story of how, as the disciples came to reflect on the life and death of Jesus Christ, he became “present” to them in a new way, through the Spirit. This, in turn, empowered them to proclaim the good news of his Gospel. Some theologians offer this as a more credible or contemporary way of understanding the “resurrection.”

But there is a problem with this idea of the resurrection as the after-effects of a “shared memory.” Certainly, after the resurrection and the ascension the disciples would have “remembered” Jesus, and certainly they may have had powerful Spirit-filled experiences as they did so, often as they gathered in community. But, to my mind, only something as vivid, dramatic and, in a word, real as the multiple appearances by the risen Christ could have moved the disciples from abject fear (cowering behind closed doors) to being willing to give their lives for Jesus. Nothing else can credibly account for the transformation of terrified disciples into willing martyrs.[↩]

- In my university German studies, we read Gotthold Ephraim Lessing‘s famous and what became normative Enlightenment dictum that There is an ugly broad ditch between the accidental truths of history and the necessary truths of reason. In other words, “historical” events so claimed by Christians such as the Resurrection are not in themselves self-evident truths compared to axiomatic truths of reason, accessible to any rational mind. Or: it is impossible to prove faith from history. Two characters in my Chrysalis Crucible novel respond thus to Lessing:

Andy replied, “There was a ‘self-evident’ truth Lessing himself was overlooking. The truth is, ‘truth’—even the ‘necessary truths of reason’—are not so obviously ‘true’ or ‘necessary’ after all.”

Dan could not hold back. “The great Michael Polanyi objection, precisely! [More on Michael Polanyi is in the next footnote.] Had Mr. Lessing been able to transport himself magically and linguistically to the head hunters roaming around New Guinea at the time, he’d have quickly found out how nonuniversally-self-evident were his ‘necessary truths’ after all, perhaps only moments before falling prey to their ‘necessary truth,’ namely, outsiders were best in the cooking pot, and his sun-shrunken head pride-of-place charm above the chief’s doorway.

James D.G. Dunn comments:

In short, the tension between faith and history has too often been seen as destructive of good history. On the contrary, however, it is the recognition that Jesus can be perceived only through the impact he made on his first disciples (that is, their faith) which is the key to a historical recognition (and assessment) of that impact . . .

It should not go unobserved that if this insight is justified it provides some sort of solution to the long-perceived gulf between history and faith. For in the historical moment(s) of creation of the Jesus tradition we have historical faith. The problem of history and faith, we might say, has been occasioned by the fact that further down the stream of faith and history the two have seemed so difficult to reconcile . . . All I am saying at this point is that the actual Synoptic tradition, with its record of things Jesus said and did, bears witness to a continuity between pre-Easter memory and post-Easter proclamation, a continuity of faith (Jesus Remembered: Christianity in the Making, Volume I, pp. 132 & 133).

In other words, the Historical Jesus Quest for 500 years has attempted to get behind the scenes of the Gospels to see what was really happening on the other side of the curtain, the axiomatic assumption since the Enlightenment generally being, what is going on in front on the Gospel stage, the actual play as recorded in the Gospels, is untrustworthy because in Lessing’s word merely “accidental.” 500 years of failure in, one may rather definitively say, the stage or front of the scenes–the play as recorded in the Gospels–is all one will ever be able to see! And in the paraphrased words of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, “the play’s the thing wherein to catch the conscience of us all . . .”

Dunn’s entire study is of a “Jesus Remembered” who is accessible equally to history and faith, wherein the only Jesus of history it is possible to discover is the Christ of faith. In light as said of 500 years of failed “historical Jesus questing,” yielding only a multiplicity of Jesuses historically “reconstructed” to look each time suspiciously like the reconstructionist him/herself is simply projecting his/her bias (or preferred “Jesus” if you will) onto the Gospels’ Jesus,

it becomes clear that a theological and cultural agenda is the driving force rather than a desire to do better history (The Writings of the New Testament: An Interpretation, Third Edition, Luke Timothy Johnson, Minneapolis:

Fortress Press, 2010, p, 629–in Second Edition).

It’s just possible then that Lessing’s “ugly, broad ditch” was needlessly dug by him and his contemporaries . . . into which many since subsequently and haplessly fell. A further discussion of Lessing’s ditch is: Leaping Lessing’s Ugly Broad Ditch.

Michael Polanyi emphasizes that personal knowledge is dependent on “communities of dialogue” within given cultural traditions which we all inhabit. It’s just that different cultural traditions yield different knowledge/rationalities.

He writes:

Articulate systems which foster and satisfy intellectual passion can survive only with the support of a society which respects the values affirmed by these passions, and a society has a cultural life only to the extent to which it acknowledges and fulfills the obligation to lend its support to the cultivation of these passions . . . The tacit coefficients by which these articulate systems are understood and accredited . . . are also coefficients of a cultural life shared by a community (Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1962, p. 203.)

Our formal upbringing evokes in us an elaborate set of emotional responses, operating within an articulate cultural framework. By the strength of these affections we assimilate this framework and uphold it as our culture… (ibid, p. 70.)

Lessing was a white adult male within an educated elite European circle of white males in the 18th century at a time of the incipient Enlightenment, whose shared rationality was moulded by that community. There is otherwise no shared universal rationality. (Widespread received rationality for instance throughout the South of the USA amongst Whites for more than a century dictated the necessity of Blacks hanging from trees.)

A helpful study that discusses Michael Polanyi and philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre together in this regard is here.

Larry Siedentop also traces in the study noted above the profound changes in the basis/understanding of “rationalism/reason” from ancient Greco-Roman culture to the modern era under the enlightened (read “liberalizing”) influence of the Church. The burden of his monograph is to demonstrate that without that influence/by continuing with ancient pagan cultural conceptualizations of rationality, there would never have been development of the Western liberal concept of the individual.[↩]

- Brilliant Catholic priest, sociologist, award-winning essayist, novelist, prodigiously prolific author (each list of his nonfiction, then fictional works alone–etc., etc., etc.!–is longer than the number of books many educated folks read in a lifetime), Fr. Andrew Greeley put it this way:

At this point, I should make clear where I am coming from. I am a Catholic Christian, indeed a priest. I believe in all the Church’s teachings about Jesus. I believe that in Him humanity and divinity are seamlessly shared, true God and true man. I believe in the virginal conception of Jesus and His physical resurrection. I’ve never seen the point in trying to water down the wonderful or the surprising in the Jesus story merely to win over those who do not believe by saying, in effect, “We are not really as outrageous as we seem.” I figure that if God is going to intervene in the human condition for a decisive event he will do it big time. If God intends this intervention to be a surprise then he will make it a big surprise. It is, after all, God’s cosmos. He who launched the Big Bang can rearrange things slightly when something truly decisive is about to happen. Thus the question did Jesus rise from the dead “physically” or “spiritually” has always seemed to me to be absurd. He rose. Period. End of revelation.

Those who argue like Bishop Spong that the Resurrection was in fact a change in the personalities and perceptions of the apostles are willing to give away the whole game because scientists say that a resurrection is impossible. But one will not win scientists to the cause of Jesus by watering down the traditional Christian conviction that the surprise of Easter Sunday was something vast, spectacular, unparalleled. My friends Hans Küng and the late Raymond E. Brown argued once at a meeting of theologians whether a TV camera would have recorded Jesus emerging from the tomb. I couldn’t see the point of the argument and still can’t. Jesus was alive again and not just in the minds of his followers. The Resurrection was not just a religious experience among the apostles who were not at the time disposed to religious experiences but rather overcome with fear and grief–like Cleopas and friend scurrying away to Emmaus. The surprise of Easter surely caused a religious experience that persists to this day. It is not the result of one. (For a lovely reflection on Fr. Greeley when he died at 85, please see: Religion Of Doubt: A Catholic Critic’s Faith Survives After His Death, June 05, 2013, by Rich Barlow.) [↩]

- Please also see this article: Katharine Hayhoe, Santa Ono featured in major science/faith conference.[↩]

- See: The God Debate–YouTube.[↩]

- See: On the Front Lines by acclaimed former CBC Correspondent Brian Stewart. He writes:

For many years I’ve been struck by the rather blithe notion, spread in many circles including the media, and taken up by a rather large section of our younger population, that organized, Mainstream Christianity has been reduced to a musty, dimly lit Backwater of contemporary life, a fading force. Well, I’m here to tell you from what I’ve seen from my “ring-side seat” at events over decades that there is nothing that is further from the truth. That notion is a serious distortion of reality. I’ve found there is NO movement, or force, closer to the raw truth of war, famines, crises, and the vast human predicament, than organized Christianity in Action. And there is no alliance more determined and dogged in action than church workers, ordained and lay members, when mobilized for a common good. It is these Christians who are right “On the Front Lines” of committed humanity today and when I want to find that Front, I follow their trail.

…

I don’t slight any of the hard work done by other religions or those wonderful secular NGO’s I’ve dealt with so much over the years. They work closely with church efforts, they are noble allies. But no, so often in desperate areas it is Christian groups there first, that labor heroically during the crisis and continue on long after all the media, and the visiting celebrities have left.

Another excellent piece making the above point, this time about the sheer radicality of the Apostle Paul is: Paul and Christian Social Responsibility. I introduce it thus:

New Testament scholar Chris Marshall first published this piece in 2000.

There is another piece on this site (Is Paul the Father of Misogyny and Antisemitism?), by Pamela Eisenbaum, Pauline scholar, practising Jew, feminist, and professor at a Christian seminary (Iliff School of Theology). She subsequently wrote Paul was not a Christian: The Original Message of a Misunderstood Apostle.

This, read conjointly with Pamela Eisenbaum’s piece above on this site, points to my belief that other than Jesus, Paul was the most radical social reformer the world has ever seen! He was decidedly not:

- misogynist

- anti-semitic

- perverse founder of a new faith called “Christianity” over against Judaism

- socially status quo

He was quite the contrary on all accounts. To read Paul is to hold unholdable for long, fiery hot potatoes! I will never recover from the sheer energy of Paul’s profound radicality! Atheist philosopher Alain Badiou also argues that the

Pauline figure of the subject still harbors a genuinely revolutionary potential today: the subject is that which refuses to submit to the order of the world as we know it and struggles for a new one instead. (from back cover of: Saint Paul: The Foundation of Universalism.)

For much on my website about the second most socially revolutionary person who ever lived, the Apostle Paul, please see here.[↩]

- You might also be drawn to some of the glorious poetry and music on Canadian award-winning singer/songwriter and recently inducted into the Order of Manitoba Steve Bell’s page: Thoughts, Songs and Poems for Easter Morning 2020.[↩]