At 30 years on to this day, April 7, 2024, the Rwanda Genocide broke out, that saw more than 1 million Rwandans murdered. CBC did the interview you see below.

Roméo Dallaire led the UN’s peacekeeping mission when more than 800,000 Rwandans — most of them Tutsis and moderate Hutus — were slaughtered by the Rwandan military and Hutu militia. Thirty years after the genocide, Dallaire criticized world leaders for seemingly not learning from past atrocities and not going ‘beyond the talk’ to intervene. Dallaire, who was also a senator, said Canada has ‘lost that extraordinary position’ of an innovator and reliable actor when it comes to international diplomacy.

Dallaire also wrote of the devastating experience in: Shake Hands With the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda. Of it:

Serving in Rwanda in 1993, LGen. Roméo Dallaire and his small peacekeeping force found themselves abandoned by the UN in a vortex of civil war and genocide. With meagre resources to stem the killing, General Dallaire was witness to the murder of 800,000 Rwandans in a hundred days, and returned home broken, disillusioned and suicidal. Shake Hands With the Devil is his return to Rwanda: a searing book that is both an eyewitness account of the failure of humanity to stop the genocide, and the story of General Dallaire’s own struggle to find a measure of peace, reconciliation and hope.

NOTE (December 13, 2022): The following article, by Jeffrey Smith | December 13, 20221, is highly disturbing about the true nature of President Paul Kagame‘s ruthlessness in Rwanda. We read:

But many retrograde African leaders–including 10 who attended in 2014—will soon touch down in Washington, walk the red carpet at the White House, and smile for photographs that will assuredly be used for propaganda purposes back home. A smiling portrait with the American president, after all, will signal to repressed citizens abroad that their pro-democracy efforts are futile. It sends the unequivocal message that no matter how hard they agitate or persevere, the U.S. will stand by their oppressors – and even shake their hands.

Perhaps no African leader plays this game of image management better than Paul Kagame of Rwanda, effectively in power since 2000—longer than the average Rwandan citizen has been alive. Kagame is among the 20 percent of African heads of state who will make a repeat appearance at this week’s summit, being billed as an opportunity to identify “shared values.” But even among this cohort of long-reigning despots and dictators, Rwanda’s president stands out as particularly cunning and ruthless in his full-throttle consolidation of political power back home—a decades-long pursuit that has been, in part, aided and abetted by the United States during successive administrations.

As Kagame once said of his political opponents, “Many of them tend to die.” So, too, has any façade of democracy in Rwanda. Since winning the country’s first direct presidential elections in 2003—with over 95% of the vote, a winning percentage that has grown to 99% in recent years—Kagame has systematically installed the structures of a totalitarian state in which literally any measure can, and will, be taken by state authorities to silence the calls for inclusivity and democratic reform—from intimidation to collective punishment and from kidnappings to ‘disappearances.’ Even state-sanctioned murder has become routine.

Kagame is right of course. About what the United States, on a far grander scale than he, since first elected in 2000, has been doing since inception. See my: The United States Is Not a Democracy. Stop Telling Students That It Is. See too: Focus on: Mapping Militarism 2022. There is also: Interaction With “The CIA: 70 Years of Organized Crime”. Then, if that is not enough, please also see my: An Open Letter to Michelle Obama, October 13, 2016; and An Open Letter To Joe Biden. In each of these posts, there are many related posts you may click on, at the end of each; etc.; etc.; etc.

Today, January 25, 2023, my friend Taylor Wilson, interviewed me about our experiences in Rwanda, for an in-house series he and others are doing for Abbotsfird Restorative Justice. The video below may be of interest.

WN: The idea of “Rwanda Dispatches” came from my friend Flyn Ritchie, editor of the online journal, Church for Vancouver, who asked me to reflect a bit on our trip to Rwanda. (Flyn eventually published excerpts here.)

WN: The idea of “Rwanda Dispatches” came from my friend Flyn Ritchie, editor of the online journal, Church for Vancouver, who asked me to reflect a bit on our trip to Rwanda. (Flyn eventually published excerpts here.)

Once we decided to attend the 2018 International CURE Conference described in my first reflection below, we thought that a 25-hour trip from Vancouver Canada warranted not returning almost immediately at the conclusion of the Conference.

The details of our stay unfolded from the initial choice to fly to Kigali:

- Stay until July 12.

- Contact three Church-based agencies in Rwanda that work with the poor and marginalized of which two responded: Good News of Peace and Development for Rwanda (GNPDR), and Prison Fellowship Rwanda (PFR).

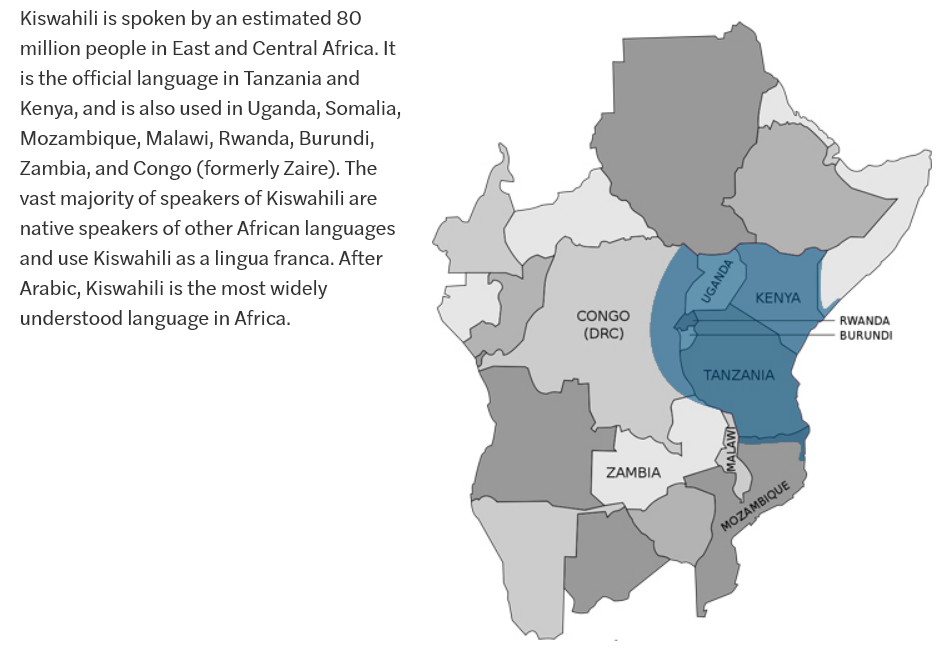

Offer our volunteer services even if significantly circumscribed by language. (Kinyarwanda is the language spoken by all Rwandans. Swahili is an international trade language (lingua franca) spoken by about 80 millions in the Great Lakes region of east/southeast Africa, namely Rwanda, Tanzania, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Somalia, Mozambique (mostly Mwani), Burundi, Uganda, Comoros, Mayotte, Zambia, Malawi, and Madagascar. Before the 1994 genocide, French was taught in all the schools, and I have used it widely enough with older people. But post-genocide schools have compulsory English classes – language immersion therefore. Of interest is a very widespread use of French first names for children born, a practice that continues into the present.

- Attempt to see through the eyes of the agencies, and in turn see through the eyes of the poor and marginalized to whom the agencies reach out.

As it turned out, we did in fact become involved with one other Church-based ministry, Transformational Ministries, subject of the first reflection below, “Rwanda Bound.”

Before continuing, it is worth airing dirty laundry first, by quoting top Irish literary critic Terry Eagleton, that:

Religion has wrought untold misery in human affairs. For the most part, it has been a squalid tale of bigotry, superstition, wishful thinking, and oppressive ideology (Reason, Faith, and Revolution: Reflections on the God Debate, Terry Eagleton, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009, p. xi). My (long) interactive book review is here.)

If one disputes this (well, maybe legitimately “for the most part”)2, one is naïve and uninformed. Or doctrinaire. But that cuts both ways.

If one disputes this (well, maybe legitimately “for the most part”)2, one is naïve and uninformed. Or doctrinaire. But that cuts both ways.

One of the best counter-narrative sweeping studies is by Sir Larry Allan Siedentop, an American-born British political philosopher with a special interest in 19th-century French liberalism. The book’s title is: Inventing the Individual: The Origins Of Western Liberalism.

A reviewer, Nicholas Lezard, writes:

Like many, I had assumed that notions of individual liberty didn’t come into play until the latter end of the Enlightenment. It was something to do with Voltaire, perhaps, or the second sentence of the American Declaration of Independence. If the Church had anything to do with individuality, it was as a brake on it, or a countermeasure. We were all just anonymous units before the power of God.

Siedentop demonstrates that the picture is much more complex. In fact, he claims, it is Christianity we have to thank, and particularly the Christianity that was being formed in the dark and early medieval ages, for our concept of ourselves as free agents. He starts in ancient Greece and Rome: there, the faculty of reason was only to be found in the ruling elite, which, in effect, meant men of a certain class in a city state. If you were a woman, merchant, or slave, all you could really use your brains for were, respectively, gossip, mercantile calculation, and unthinking obedience. (A glance at newsagents’ shelves these days may make you suspect that civilisation has gone retrograde in these respects, but let us pass on that for the moment.) Even philosophers, who had no direct allegiance to a specific place, were for a while suspect. However, seeds were sown, and things got interesting when Greek- and Latin-speaking urban dwellers around the Mediterranean started encountering the Jewish diaspora:

“Just what was it that, rather suddenly, made Jewish beliefs so interesting? It was partly a matter of imagery. The image of a single, remote and inscrutable God dispensing his laws to a whole people corresponded to the experience of peoples who were being subjugated to the Roman imperium.”

This is the beginning of a thoughtful jaunt through several centuries of developing theological and legal thinking. The stars are Augustine, Duns Scotus and William of Ockham: he of the famous Razor, the injunction that “it is futile to work with more entities when it is possible to work with fewer”. (Here, the entities concerned were demons, but the principle “a plurality must not be asserted without necessity” came to be quickly understood as very much more widely applicable.)

This is not a book to take on a beach holiday; it is chewy, involved stuff, and if at times it looks as though Siedentop is repeating himself, you may well be grateful, as I was, because you might not have got it first time round. I have never hitherto had to think about, for example, medieval corporation law and its relation to ecclesiastical authority. But the book is, once you get past the superficial difficulties, not too hard to grasp, and its basic principle – “that the Christian conception of God provided the foundation for what became an unprecedented form of human society” – is, when you think about it, mind-bending.

There is another book I highly recommend: Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World.

There is another book I highly recommend: Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World.

Of it, we read in Wikipedia:

The book is a broad history of the influence of Christianity on the world, focusing on its impact on morality – from its beginnings to the modern day.[1] According to the author, the book “isn’t a history of Christianity” but “a history of what’s been revolutionary and transformative about Christianity: about how Christianity has transformed not just the West, but the entire world.”[2]

Holland contends that Western morality, values and social norms ultimately are products of Christianity,[1][3][4] stating “in a West that is often doubtful of religion’s claims, so many of its instincts remain — for good and ill — thoroughly Christian”.[5] Holland further argues that concepts now usually considered non-religious or universal, such as secularism, liberalism, science, socialism and Marxism, revolution, feminism, and even homosexuality, “are deeply rooted in a Christian seedbed”,[6][7][8] and that the influence of Christianity on Western civilization has been so complete “that it has come to be hidden from view”.[1][7]

It was released to positive reviews, although some historians and philosophers objected to some of Holland’s conclusions.

Background

Tom Holland has previously written several historical studies on Rome, Greece, Persia and Islam, including Rubicon, Persian Fire, and In the Shadow of the Sword.[9] According to Holland, over the course of writing about the “apex predators” of the ancient world, particularly the Romans, “I came to feel they were increasingly alien, increasingly frightening to me”.[10] “The values of Leonidas, whose people had practised a peculiarly murderous form of eugenics and trained their young to kill uppity Untermenschen by night, were nothing that I recognised as my own; nor were those of Caesar, who was reported to have killed a million Gauls, and enslaved a million more.”[1] This led him to investigate the process of change leading to today, concluding “in almost every way, what makes us distinctive today reflects the influence over two thousand years of the Christian story”.[10]

Prefiguring the book, in 2016 Holland penned an essay3 in the New Statesman describing how he was “wrong about Christianity”.[11][12]

“Every sensible man,” Voltaire wrote, “every honourable man, must hold the Christian sect in horror.”

Even Voltaire might have been been critiqued by my in-laws for his failure to use inclusive language. . . — not knowing their political correctness is (generally by me welcome) product of Christian ethics.

Holland writes in response:

As such, the founding conviction of the Enlightenment – that it owed nothing to the faith into which most of its greatest figures had been born – increasingly came to seem to me unsustainable.

One must quietly, respectfully but surely ask:

Who are the dogmatic “fundamentalists” here, proverbial heads resolutely stuck in the sands of historical/historiographical ignorance?

Another philosopher-historian, William Cavanaugh, in The Myth of Religious Violence: Secular Ideology and the Roots of Modern Conflict, counters our ubiquitous Western notion that “religion” (Christianity) historically, and in resurgent worldwide Islam, is indisputably invariably violent. Cavanaugh asserts on the contrary that the claim that “religion is … essentially prone to violence is one of the foundational legitimating myths of the liberal nation-state (p. 4).”

Conventional wisdom implies that “religions” such as Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Judaism over against “ideologies and institutions” such as nationalism, Marxism, capitalism, and liberalism, are “essentially more prone to violence – more absolutist, divisive, and irrational – than the latter.” In response, the author is blunt: “It is this claim that I find both unsustainable and dangerous (p. 6, emphasis added).” “Violence” in relation to those cited in the book “generally means injurious or lethal harm and is almost always discussed in the context of physical violence, such as war and terrorism (p. 7).”

Not only does the author use the term “myth” to indicate the claim is false, “but to give a sense of the power of the claim in Western societies (p. 6).”4 The claim seems a given and inevitable – and therefore difficult to refute. (From my Book Review of the above book and another by Cavanaugh. You may also listen to him interviewed by David Cayley, in a series entitled: After Atheism: New Perspectives on God and Religion. It was designed initially as a 12-part series, the second set of interviews entitled The Myth of the Secular. The listener is in for a veritable feast of ideas spanning a 30-plus year career of programs produced for CBC Ideas by David Cayley. The two programs just mentioned were David Cayley’s last offerings before retirement. Do see his superb website by clicking on his highlighted name. There is much written material as well.)

As such, the founding conviction of the Enlightenment – that it owed nothing to the faith into which most of its greatest figures had been born – increasingly came to seem to me unsustainable. – Tom Holland

Again, I have relatives who are so fundamentalist (read dogmatic) about their dearly held embrace of said Enlightenment mythology, that there is no way in to even engage them with such a thoroughly researched and documented set of theses as noted in the two books above. Sadly, one is at a loss about what to do with such blind prejudice other than allow those so self-duped to simply stew in the juices of their uninformed biases. Quidquid recipitur, ad modum recipientis recipitur. The recipient must be at least open to possible attunement with the message, or miss it altogether! In their cases, they have jettisoned an earlier religious fundamentalism only to display Phoenix-like its quintessential spirit in virulent, even arrogant anti-Christian sentiment.

The above highlights a more general problem with the recent spate of neoatheistic writings. Renowned Irish literary critic Terry Eagleton engages such obstinate — even silly — dogmatism in Reason, Faith and Revolution: Reflections on the God Debate. My interaction with the book may be found by clicking on the title. Another pertinent article by John Mark N. Reynolds is: “The Five Worst “Arguments” (or Claims) Made by Internet Atheists.”

For more on this, please view the following quotes:

Assumptions that I had grown up with—about how a society should properly be organised, and the principles that it should uphold—were not bred of classical antiquity, still less of ‘human nature’, but very distinctively of that civilisation’s Christian past. So profound has been the impact of Christianity on the development of Western civilisation that it has come to be hidden from view. It is the incomplete revolutions which are remembered; the fate of those which triumph is to be taken for granted.—Tom Holland in Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World, pp.16 & 17.

The relationship of Christianity to the world that gave birth to it is, then, paradoxical. The faith is at once the most enduring legacy of classical antiquity, and the index of its utter transformation. . . It has long survived the collapse of the empire from which it first emerged, to become, in the words of one Jewish scholar, ‘the most powerful of hegemonic cultural systems in the history of the world’ (A Radical Jew: Paul and the Politics of Identity, Daniel Boyarin, p. 9.)—Tom Holland in Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World, pp. 10 & 11.

Christianity’s principles . . . continue to dominate much of the world; Tom Holland’s thoughtful, astute account describes how and why . . . An insightful argument that Christian ethics, even when ignored, are the norm worldwide.—Kirkus (starred review)

When we condemn the moral obscenities committed in the name of Christ, it is hard to do so without implicitly invoking his own teaching.—Irish literary critic Terry Eagleton in: Dominion by Tom Holland, review – the legacy of Christianity

Modern reformers complain, quite justly, about the violence of Christianity, René Girard says, but they fail to notice that “they can complain [only] because they have Christianity to complain with.”—David Cayley in Ivan Illich: An Intellectual Journey, p. 404.

A little learning is a dang’rous thing.—Alexander Pope

Please also see, by Peter Wehner, December 24, 2019, Christmas Turns the World Upside Down: What does it mean for God’s power to be “made perfect in weakness”?

The Judeo-Christian Tradition is a formidable repository for thousands of years of brilliant thinkers. A little bit of humility on the part of Christianity’s “cultured” despisers, and a whole lot of further study and thinking (“A little learning is a dangerous thing;/Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring:” — Alexander Pope) just might be the order of the day… One can hope it at least might give such despisers pause…

On the other hand (there is always a dialectic) one can cite award-winning, retired Canadian journalist Brian Stewart of the Canadian Broadcasting Commission (CBC), who in “On The Front Lines” remarks:

“I’ve found there is NO movement, or force, closer to the raw truth of war, famines, crises, and the vast human predicament, than organized Christianity in Action.”; and again: “I don’t slight any of the hard work done by other religions or those wonderful secular NGO’s I’ve dealt with so much over the years… But no, so often in desperate areas it is Christian groups there first, that labor heroically during the crisis and continue on long after all the media, and the visiting celebrities have left.

It seems that “religion” when it is bad can be as evil as it gets. When it is good however, it produces towering saints as good as they get, such as Mahatma Ghandi, Martin Luther King Jr., and Mother Teresa – to choose some 20th-century examples. There are myriad others, one of whom you will meet if you read on, is retired Anglican Bishop John Rucyahana of Rwanda; and a vast multitude of the self-deprecating unsung to whom Brian Stewart alludes.

Three books telling further remarkable stories are: Blessed Among All Women: Women Saints, Prophets, and Witnesses for Our Time; Blessed Among Us: Day by Day with Saintly Witnesses; Subversive Orthodoxy: Outlaws, Revolutionaries, and Other Christians in Disguise. The first two are by Robert Ellsberg; the last by Robert Inchausti.

It is of course ludicrous to dismiss the Bible/Christianity or any other holy book/religion based on its worst exemplars, as Eagleton observes:

Besides, critics of the most enduring form of popular culture in human history [i.e. religion] have a moral obligation to confront that case at its most persuasive, rather than grabbing themselves a victory on the cheap by savaging it as so much garbage and gobbledygook. The mainstream Christian theology I have outlined here may well be false; but anyone who holds to it is in my view deserving of respect… Ditchkins [conflation of atheists Christopher Hitchins and Richard Dawkins, whose writings he playfully lampoons repeatedly], by contrast, considers that no religious belief, anywhere or anytime, is worthy of any respect whatsoever. And this, one might note, is the opinion of a man deeply averse to dogmatism.

Insofar as the faith I have described is neither stupid nor vicious, then I believe it is worth putting in a word for it against the enormous condescension of those like Ditchkins, who in a fine equipoise of arrogance and ignorance assert that all religious belief is repulsive (pp. 33 & 34).

As to historic Christianity in the context of world religions, the 2019 reissued volume by Ron Dart and J. I. Packer, Christianity and Pluralism, a response to former Bishop Michael Ingham’s Mansions of the Spirit, is at once charitable, informative and thought-provoking — while holding to Christian distinctiveness. Christopher Marshall in “Paul and Social Responsibility” writes:

Stanley Hauerwas has suggested [‘The Moral Authority of Scripture: the Politics and Ethics of Remembering’, Interpretation 34 (1980), pp 356-70.] that the only thing that makes the Christian church different from any other group in society is that the church is the only community that gathers around the true story. It is not the piety, or the sincerity, or the morality of the church that distinguishes us (Christians have no monopoly on virtue). It is the story we treasure, the story from which we derive our identity, our vision, and our values. And for us to do that would be a horrible mistake, if it were not a true story, indeed the true story, which exposes the lies, deceptions, and half-truths upon which human beings and human societies so often stake their lot.

Dart’s and Packer’s book points to the same understanding. Or as J.R.R. Tolkien arrestingly writes in a presentation to fellow philologists, employing his neologism, eucatastrophe:

“In [a true fairy-story] when the sudden ‘turn’ [or ‘eucatastrophe’] comes we get a piercing glimpse of joy, and heart’s desire, that for a moment passes outside the frame, rends indeed the very web of story, and lets a gleam come through… The Birth of Christ is the eucatastrophe of Man’s history. The Resurrection is the eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation ( J.R.R. Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories)”.

In Webster’s Dictionary, there are two sequential entries, first on “realpolitik”, next on “real presence.” Realpolitik is “politics [or life!] based on practical and material factors” – upon the routine story the world tells about the violence and counter violence on which all “civilization” ultimately rests. Christ’s “real presence realpolitik” is about the preposterous Story the Gospels tell about the Incarnation and Resurrection on which the Kingdom of Peace — humanity’s destiny — ultimately rests.

The Birth of Christ is the eucatastrophe of Man’s history. The Resurrection is the eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation (J.R.R. Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories).”

I thought to get the above out of the way first.

To the point: my wife and I have been profoundly impacted by the dedication, creativity, and as Brian Stewart paraphrased puts it, sheer “love in action” of the Church-based agencies with which we work here in Rwanda. Stewart said this just before the above quote:

For many years I’ve been struck by the rather blithe notion, spread in many circles including the media, and taken up by a rather large section of our younger population that organized, mainstream Christianity has been reduced to a musty, dimly lit backwater of contemporary life, a fading force. Well, I’m here to tell you from what I’ve seen from my “ring-side seat” at events over decades that there is nothing that is further from the truth. That notion is a serious distortion of reality.

And freelance Canadian Columnist Barbara Kay wrote this on June 22, 2005 in Canada’s National Post:

The Christian faith, uniquely among the world’s religions, has inspired an awesome tradition of ministering to the lepers most of us cannot bear to look at.

Again, in an April 21, 2005 article in the National Post, in response to the willfully and woefully ignorant (of academic studies about CoSAs (see below) immense success) Harper government decision to discontinue what was shoe-string funding anyway, she wrote:

Most CoSA volunteers are Christian and see their work as a religious calling, although they scrupulously avoid evangelizing in their work with offenders.

What struck me about CoSA when I first ran across it some 10 years ago is the fact it is work only people of religious faith would do. There are some forms of public service that are so difficult they can only be motivated by the sincere belief that within all of us — even pedophiles — there is some divine grace that deserves forgiveness and nurturing. Many progressives wish religion would disappear utterly from the public forum. But I daresay there are precious few secular progressives who would commit to “walk with” (as CoSA puts it) the men in the CoSA program for hours every week, year after year, to ensure they do not reoffend.

Kay was writing about a program first developed in Canada, designed to work with Canada’s still current ultimate pariahs – released high risk sex offenders – when rape and murder accomplice Karla Homolka, had asked for such a Circle. I can nonetheless vouch for the profoundly Christian origins of Circles of Support and Accountability (CoSA) in Canada, a highly successful Restorative Justice program (Restorative Justice in its use of mediation worldwide is another Canadian first, and also has profoundly Christian origins – long since with worldwide impact), based on numerous evidence-based studies in Canada and elsewhere.

I in fact sit on the national Board that last year received $7.5 million from Public Safety Canada for five years, to assist in the operation of 14 such programs spread out across Canada. Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale in speaking at the national program’s official launch November 2017, cited those studies in part for his Department’s (through National Crime Prevention Strategy) granting that funding. A high percentage of those currently active in CoSA Canada and its related sites are “religious”: specifically are motivated by Christian faith.

And yet I have friends to whom I have directed attention to the above (such) articles, not to mention having had many discussions with them over the years on this, who like the worst of religious fundamentalists, dogmatically dismiss the institutional Church. Perhaps they should read Terry Eagleton’s book (or my review/interactions with it) to see how rigidly and one-sidedly doctrinaire they sound, sadly (and all unawares) worthy indeed of Eagleton’s playfully conflated epithet about Hitchins and Dawkins: Ditchkins – that is to say in the end on this matter (my interpretation) brittle bumpkins.

Charles Dickens began his famous novel, A Tale of Two Cities, with:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

Surely this speaks to the nature of human history and to the human condition! Universities and the brightest scientists split the atom, thereby unleashing on humanity and the planet permanent threat of utter annihilation… And with madman Trump, we came perilously close, remain so with him at the helm of the US stockpile of nuclear weapons capable of destroying all sentiate life on the planet many times over. Hell, not just madman Trump, but madman Uncle Sam, and all other states prepared to use such beyond-the-pale evil weaponry.

And the same kinds of “honourable” family-loving and cultured scientists, like Nazi guards who committed horrors by day and came home, hugged their kids and went off to the Opera by night with their wives, have developed the most diabolical weapons known to humanity… I could go on and on… One need only read historian Alfred McCoy’s newest book about the witch’s brew of cyber horrors being concocted by those same kinds of Nazi-like scientists under the watchful eyes of the Nazi-like US government (that currently is dropping bombs on all manner of innocents somewhere outside America – so far – every 12 minutes) to get it about the leading current “democracy” (and we in the West deeply embedded with it) blithely carrying out mass slaughter on a scale beyond diabolical – if that’s possible!

One should rightly rail against all Nazi Doctors of Death, and the brutal tens of thousands of Rwandan killers (and worse). Do we also then rail against all doctors, against all scientists? Against all universities? Against all governments? The point could be made in any number of ways.

Here is one more: Were a Martian to visit our Planet to study humanity, his report back home might be that humanity is hopelessly given to perpetual and horrific violence. And he would be right – as far as it goes.

But he of course would be wrong if he stopped there – beyond-the-pale wrong!

The Church and all religions participate in the human condition equally with the best and the worst of us, and of humanity’s institutions. Of course there are exclusionary dynamics present in the Church! What human institution/collective/society/government does not have such?! Boundaries are the very stuff of the human enterprise. However, in the case of the Story of Jesus, anthropologist René Girard asserts that the human condition is across Time and Planet ubiquitously mimetic in its violence and scapegoating, to which the Jesus Narrative provides the Way out. In that Way, Jesus taught his followers (should-be imitators) to draw a Circle of Inclusion around enemy and friend/family alike, and ceaselessly (like God in Christ’s Atonement – see Romans 5:6 – 11; Ephesians 5:1 & 2) invite everyone in. Now that is world-shaking Good News!

“The Church is a great totalitarian Beast with an irreducible kernel of Truth.”–Simone Weil

So back to the Church. 20th-century mystic Simone Weil, who never joined the institutional Church, but was finally baptized, wrote that “The Church is a great totalitarian Beast with an irreducible kernel of Truth.”5 And of course Jesus is that Truth! I can go with that – though my wife and I are gratefully part of a Mennonite Church.

And there is an African proverb that goes: “The Church is hopeless. The Church is the only Hope.” I can go with that too, thereby acknowledging the dialectic of human experience, not least of the very human institution – in often enough not-so-healthy myriad shards – called Church.

Caroline Casey (host of the “Visionary Activist” radio program on www.kpfa.org) remarked: “The church is an ordeal – Take the sacraments and run! ” I understand that sentiment too!

Maybe that is a sufficiently far-afield introduction to the Rwandan reflections below: glimpses indeed of believers caught up in the messy Story called Church; and seeing through Church-ministry eyes something of God’s amazing Grace at work in a land that is haunted everywhere by horror and tragedy – and will remain so for a long time to come.

§§§

Reflections on a Joyful Journey: Rwanda Bound

June 1, 2018

Last year we learned that the 2018 International CURE Conference (to encourage human rights and prison reform worldwide) was to be held in Kigali Rwanda. (A CURE 2018 International Conference Resolution was sent at Conference end to the United Nations and to the media.)

We wondered if the invitation from 2017 attendee Pius Nyakayiro (I will tell some of his story in Dispatch 4) would have the support and means of pulling it off – not for lack of ability but of funds and time. Pius did! And what an outstanding Conference in every way it turned out to be!

In that we had for the first time attended that Conference the year before in Costa Rica and loved it, in that we still had enough Aeroplan mileage points to pay for our trip, in that in particular Esther has had a yearning to travel (for the first time for us both) to somewhere on the continent of Africa, it seemed the perfect opportunity!

To get to our point of departure at Vancouver Airport Wednesday May 16 at 1:30 p.m., we had to:

- get immunized (lots – and lots of fun!);

- prepare a joint presentation on the End Abuse Program of Mennonite Central Committee of British Columbia: specifically Esther shared on the trauma recovery facilitation she and her co-facilitator Kathy Moodie, a professional counsellor, have done in Fraser Valley Institution, with women who have been in abusive relationships. The institution is one of five federal women’s prisons located in the five Correctional Services Canada regions. (This is the only such program.) And we shared as well about the 15-session “Home Improvement” work we do for men causing the abuse;

- read as much as possible about Rwanda, in particular about the 1994 genocide. (In that regard, we recommend three outstanding of many publications: Road Trip Rwanda: A Journey Into the New Heart of Africa by Canadian Will Ferguson;: As We Forgive: Stories of Reconciliation from Rwanda by American Prison Fellowship staff person (based on a movie of the same title) Catherine Claire Larson; and A People Betrayed: The Role of the West in Rwanda’s Genocide by British journalist Linda Melvern.)

We knew from the outset that we did not wish to visit Rwanda as tourists, who tend to see from on high distant countries through eyes of wealth and privilege, but in that we were travelling such a vast distance (25 hours on three flights: Vancouver to Frankfurt, to Istanbul, to Kigali), we offered as volunteers rather to see the country through the eyes of two Christian service agencies: Prison Fellowship Rwanda; and Good News of Peace and Development for Rwanda. We however cannot kid ourselves: we are here in any event because of (comparative) wealth and privilege!6 Or as our Canadian indigenous peoples tell us: Just because you are in time living downstream from the brutality of your European ancestors does not mean you do not continue to be beneficiaries.

We are in Africa therefore as “Mzungus” (Kiswahili for whites of European descent) who have been beneficiaries of European colonization (read again brutal Empire-building), where evangelism was done too often in the wake of “gunboat diplomacy” that “pacified” (murdered) resistant locals.

As many knowledgeable Christians here will quietly assert: the gift of the Gospel was mixed with the blood not only of Christian martyrs (there were indeed some!), but also with far too much blood of chiefs, other leaders, and their people. (May God have mercy!) This apart from the barbaric slave-trade… Though Rwanda thankfully was not directly impacted by it, situated at the heart of Africa just below the equator, unreached by any Europeans until 1894 – after (in law but not in practice) slavery was abolished in Europe and North America. Colonization however meant embracing a track of slavery’s first cousin: brutal subjugation and oppression of a people to maximize domination to extract maximum wealth. This was modus operandi the world over by Europeans and too often with Christian missionaries’ consent (and that of their converts): in direct contradiction of Jesus:

Jesus called them together and said, “You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their high officials exercise authority over them. 26Not so with you. Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant, 27and whoever wants to be first must be your slave— 28just as the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.” (Matthew 20: 25 – 28)

I will end this dispatch with brief mention (more to follow) of an outstanding Anglican Bishop, John Rucyahana, a 72-year-old man who has given his life in ministry to and love for people in Uganda and in Rwanda, and by extension throughout the continent and world, and who since retirement continues to do so! To us, after spending many hours with him, he exemplifies Jesus’ challenge above.

He founded (amongst many other church enterprises) with others, Transformational Ministries, based in the city of Musanze, about two hours north of Kigali, in the country of “a thousand hills”, near the Virunga volcanoes mountain range, and near the border of Uganda. (We loved the beautiful bus ride there!) We had known nothing of this four-year-old ministry before arriving. You can hear the Bishop tell of the ministry on this website, and also read about his longstanding servant career. Two biographies about him have also been written: The Bishop of Rwanda by John Rucyahana and James Riordan, and Jesus: Hope of the Nations by Mary Weeks Millard.

One of the many needs of this ministry is: supplying a cow to each family of the poorest and most marginalized/rejected of Rwandan Society – the Batwa (or Twa), the pygmies/bushmen/hunters and gatherers of Rwanda. The deal is: each family who receives the gift of a cow must build a shelter for it, care for it well, and pass on any calf to another Twa family, thereby making the gift multiply like the five-and-two miracle Jesus performed. This so far has been fifteen and four!

Many in their prejudice predicted that the Twa would likely sell or butcher the cow for quick food or cash, and never comply with the requirements. They have been proven wrong! Esther and I were privileged to visit many cow-recipient families (otherwise visited in remote places twice a week by staff), and hear expressions of gratitude each time for this amazing ministry. The recipients are also being integrated into wider Rwandan society, and are being sponsored to send their kids to school as well: an uphill struggle, since so many older kids stay home to care for the younger ones, and because of chronic hunger… One Twa recipient later sang a simple song of gratitude for Bishop John and this ministry.

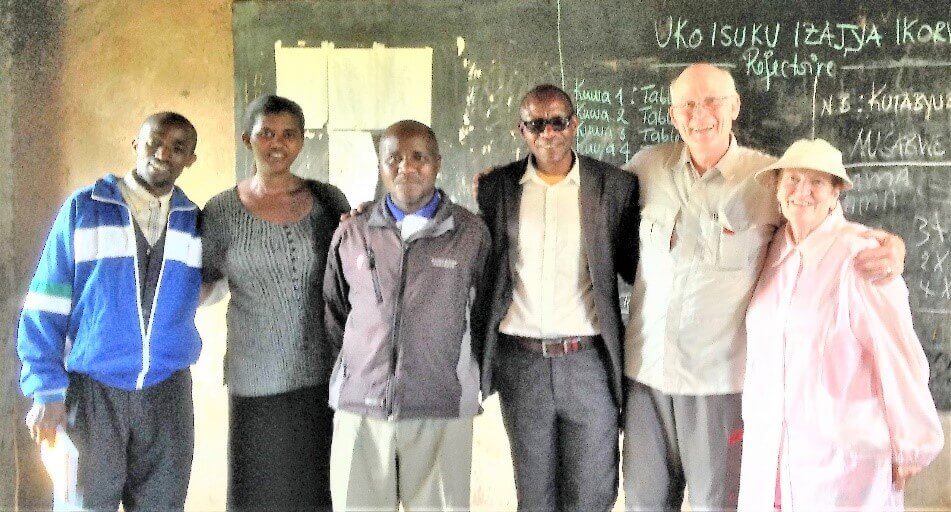

a school with TM Staff and the principal shown, where Twa kids are being successfully integrated into, and kept going to school

If you wish to contribute towards this shoe-string-budget ministry (which does and wishes to do so much more! – please do read about it!) you may find out how by clicking on the website then clicking on the “Donate” button. It describes the various ways such support is used. The cost of the cow itself is about USD$250. Add another USD$250 to help with shed-building materials. To support one child in school for a year–that covers a school uniform, a backpack, school supplies, and a daily hot lunch–is $86 USD. We also know this ministry to be absolutely authentic! We have seen it with our own eyes7. (Like Jesus who invited people to “come and see”).

You are of course also welcome to correspond with us for further sharing: Esther & Wayne Northey – please use the “Contact Me” page.

Next missive: the amazing work of reconciliation going on in this country, against the backdrop of the 1994 genocide, of which Bishop John has been an outstanding leader! We can learn much!

§§§

Dispatch 2: Reconciliation Rwanda Style

Introduction

It is almost impossible to know where to begin in discussing the exceedingly complex reality of Rwandan reconciliation work post-genocide…

Consider:

- A people in pre-colonial times with three distinct groups of inhabitants: Tutsi, Hutu, Batwa (Twa – also known as “Historically Marginalized People” – HMP). They are further known as pygmies and bushmen. However, the same culture and language overall were shared, with predominantly fluid distinctions related to relative wealth.

- The main Rwandan cultural distinction was between the Batwa, as primarily hunter-gatherers, and the others who either kept cattle or farmed. The Batwa are the oldest known inhabitants of the Great Lakes Region of Central Africa and are found also in Burundi, Uganda, and the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They are not unlike North American indigenous people, except they have no distinct physical differences apart from generally smaller stature.

- The estimated number of HMP living in Rwanda lies between 33,000 and 35,000, i.e. around 0.4% of Rwanda’s population. I wrote an earlier dispatch about the amazing four-year-old “Transformational Ministries”, begun by retired Anglican Bishop John Rucyahana: a great man of prayer, a great man of God, a great man.

left to right: Christine Kinkandi (personal assistant for Bishop John) , WN, EN, Bishop John, Claude Iyakaremye (responsible for evangelism)

In pre-colonial times, Rwanda occupied a much larger land mass, and had had a monarchical government which was divided up under colonial rule, thereby reducing significantly the size of the country, and concomitantly lessening the power of the king to amass a force to resist the colonizers: a classic colonial strategy of “Divide and Conquer”. Theirs had been a sophisticated system of governance that had worked well for centuries. Quoting from a Wikipedia article:

A traditional local justice system called Gacaca predominated in much of the region as an institution for resolving conflict, rendering justice and reconciliation. The Tutsi king was the ultimate judge and arbiter for those cases that reached him. Despite the traditional nature of the system, harmony and cohesion had been established among Rwandans and within the kingdom since the beginning of Rwanda.

The distinction between the three ethnic groups was somewhat fluid, in that Tutsi who lost their cattle due to a disease epidemic, such as Rinderpest, sometimes would be considered Hutu. Likewise Hutu who obtained cattle would come to be considered Tutsi, thus climbing the ladder of the social strata. This social mobility ended abruptly with the onset of colonial administration.

More will follow about the Gacaca.

The final phrase “colonial administration”, though likely not intentional, is euphemistic ruse for “Empire-building” – the primary goal of all colonization – throughout human history. And Empire is invariably about two things, the former leading to the latter: domination and maximally amassing wealth. The former is ultimately amoral and brutal, the latter deeply rapacious: colonization “red in tooth and claw” – Tennyson in different context. Two outstanding theological studies on Empire, one by a noted Jewish Christian theologian Wes Howard-Brook, the other by a noted Palestinian Christian theologian Mitri Raheb are:

“Come Out My People!”: God’s Call Out of Empire in the Bible and Beyond and Faith in the Face of Empire. The website I keep since retirement that you are on is dedicated to the Gospel as Counter-Narrative to Empire.

Bishop John notes that under colonial rule, Rwandans were reduced to slavery or worse, through forced conscription, for instance to build roads – public works that were harshly enforced. He writes:

Like all colonial masters, the Belgians exploited African resources. There was very little regard for Africans as human beings. The colonizing nations believed the African brain did not function like their own brains, and saw them as second-class beings, somewhere between themselves and the animals in the jungle… It’s not a great loss to lose ten thousand or even a million of these subhuman people to build the road. They have to serve the superior humans. (Rucyahana, John. The Bishop of Rwanda, Thomas Nelson. Kindle Edition, pp. 11 & 12, & 16).

In 1894 the first European, a German Count, set foot in Rwanda, and by 1897 it was a German colony – even if the Rwandan people did not know it at the time! One hundred years later, in 1994, genocide horror engulfed the nation. Very briefly below is some of the back story.

The Road to Genocide

At the end of World War I, the newly-formed League of Nations assigned rule of Rwanda to Belgium. Deep racial bias based on completely specious “science” attributed the minority Tutsi with superior human traits, because, it was claimed, of their presupposed naturally superior Caucasian ancestry. This same “science” was introduced by the Nazis in 1931, and the horror of Holocaust began…

The Belgians issued identity cards to differentiate Tutsi from Hutus in 1933. Jump ahead to April 1994, and Tutsi identity cards had become death warrants, when in 100 days upwards of one million Tutsi were mercilessly and gruesomely slaughtered – at five times the rate the Nazis massacred the Jews. Many church denominations had priests and pastors, nuns and lay persons and others, betraying their flocks and fellow congregants, luring them to their churches with promises of protection, aiding and abetting the killers, participating directly in the killings. Priests bulldozed their churches to crush to death the Tutsi who had fled there for safety. Nuns provided gasoline to burn churches and those sheltered inside. Some said of this horror that “the blood of [false] ethnicity was thicker than the water of baptism.” In fact, Princeton University scholar Mahmood Mamdani writes:

Let us recall that there was no single institutional home, no mortuary, bigger than the Church for the multiple massacres that marked the Rwandan horror. After all, but for the army and the Church, the two prime movers, the two organizing and leading forces, one located in the state and the other in society, there would have been no genocide (When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda“, Mahmood Mamdani, Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 232-33; quoted in “Implication of Religious Leaders in Mimetic Structures of Violence: The Case of Rwanda“, Vern Neufeld Redekop and Oscar Gasana, Saint Paul University, Ottawa, Journal of Religion & Society Supplement Series 2, The Kripke Center 2007, pp. 117 – 137).

Mamdani writes elsewhere:

Rather than a passive mirror reflecting tensions, the Church was more of an epicenter radiating tensions” (p. 226).

Neufeld’s and Gasana’s paper states:

Rakiya Omaar, Director of African Rights, sent an open letter to Pope John Paul II, listing the most shocking instances of clergy organizing massacres, and summed up participation of the Church in the genocide:

“Christians who slay other Christians before the altar, bishops who remain silent in the face of genocide and fail to protect their own clergy, priests who participate in the murder of their parishioners and nuns who hand people over to be killed cannot leave the Church indifferent” (Mamdani, p. 227).

With reference to Mamdani’s book, the publisher notes:

“When we captured Kigali, we thought we would face criminals in the state; instead, we faced a criminal population.” So a political commissar in the Rwanda Patriotic Front reflected after the 1994 massacre of as many as one million Tutsis in Rwanda. Underlying his statement is the realization that, though ordered by a minority of state functionaries, the slaughter was performed by hundreds of thousands of ordinary citizens, including even judges, human rights activists, and doctors, nurses, priests, friends, and spouses of the victims. Indeed, it is its very popularity that makes the Rwandan genocide so unthinkable. This book makes it thinkable.

This perversion was widespread through years of teaching Hutu superiority by the government from 1959 on, and by the churches, too many in lockstep with the Belgian colonizers. And, one might add, the Prince of Peace and with it peace theology (the heart of the Gospel) were nowhere to be found… Too many churches, in particular the Roman Catholic Church, had identified with majority “Hutu Power” and The Hutu Ten Commandments, first published in a Hutu newspaper in 1990: racist and xenophobic to the core. And of course it was not “just” genocide – singular, it was murders committed well over a million times. The earlier Wikipedia article notes:

A history of Rwanda that justified the existence of these racial distinctions was written [by the Belgians first]. No historical, archaeological, or above all linguistic traces have been found to date that confirm this official history. The observed differences between the Tutsi and the Hutus are about the same as those evident between the different French social classes in the 1950s. The way people nourished themselves explains a large part of the differences: the Tutsi, since they raised cattle, traditionally drank more milk than the Hutu, who were farmers.

The 1994 genocide also left Rwanda in complete ruins politically, physically, socially, psychologically, sociologically, spiritually, and more. That like a Phoenix Rwanda has arisen from the ashes is a widely acknowledged “miracle” on multiple fronts. For instance, the capital city, Kigali, is today a modern, spacious city with wide boulevards, an excellent road system, and many modern buildings. From health care to education to social welfare, and so on (the list is long), Rwanda has positively exploded with resolve, creativity and incredible success. There is both a “Vision 2020” and a “Vision 2050” set of ambitious goals, not least to encourage growth of an expanding middle class. And there I leave the story. More of that recounting is in the Wikipedia article cited above. The continuing story is so much more complicated, begs so many questions, and I am far from competent to tell it. Though many have – which an online search will copiously reveal.

Reconciliation

Reconciliation grew out of the Rwandan horror, at once Christian-based, government-promoted, business-blessed, with aspects generically Rwandan. We learn in Willard Swartley’s exhaustive and peerless study of peace (eiréné) in the New Testament, Covenant of Peace: The Missing Peace in New Testament Theology and Ethics, that peace, peacemaking and peace-building are central to the New Testament witness, the heart of the Gospel, and the ground of the New Testament’s unity. For example, over against others’ readings of Paul, Swartley argues persuasively that this is especially so of the great Apostle. The word “reconciliation” captures this central peace/eiréné/shalom dynamic. One way to understand humanity’s primordial loss of relationship to God described in the Book of Genesis is as a profound break in relationship with God. Flowing from that original break (theological) were further breaks:

- with oneself (psychological)

- with others (sociological);

- with the Good Creation (ecological/cosmological)

For humanity ever to live fully freely, meaningfully, joyfully and abundantly, all these breaks need mending and tending, must undergo radical healing, as surely as broken bones needs crucial medical attention. One could say even that as with crime which is also defined most simply as a break in relationship, so in all these breakdowns of relationship (in the “old creation”), what is so centrally needed is a process of “restorative justice” to realign, readjust, bring restoration and healing to, all the related brokenness.

The recent Bible translation The Voice repeatedly translates Paul’s term for justice (dikaiosuné) in the book of Romans as “restorative justice”, to highlight that Paul’s justice is ever dynamically about healing broken relationships. And Paul’s challenge to all who are “in Christ” and a “new creation” (II Corinthians 5:17 – 21) is to be ambassadors of reconciliation. Dr. Swartley underscores the action component of New Testament peacemaking: not those merely “ready for peace” (Martin Luther’s status quo German translation), rather the active, creative, risking, persistent, etc., of peacemakers who continually put body and soul on the line to draw others into a restored circle of friendship, just like God in the atonement that is to be emulated – according to Romans 5:6 – 11 and Ephesians 5:1 & 2.

A succinct article, “Paul and Christian Social Responsibility” by New Testament scholar Chris Marshall, captures this admirably. (Along this same line, reviews of his outstanding comprehensive publications on Restorative Justice can be found here and here.) One can argue that post-genocide Rwanda took a page directly from the New Testament, in particular from Paul the Apostle in its approach to the profound need for the healing of Rwandans, of the nation of Rwanda. And in fact, Bishop John Rucyahana was one of those who invariably referenced Jesus and Paul in his outstanding contributions to the work towards rebuilding/reuniting the people of Rwanda. In 1995 Prison Fellowship Rwanda (PFR) began its post-genocide work. Its then and continuing Board Chair has been Bishop John. In 1999 the National Unity and Reconciliation Commission (NURC) was founded by the government to promote what the name indicates. Bishop John Rucyahana is its current President too. PFR’s mission statement is:

left to right: Bishop John Rucyahana, Charlie Sullivan – founder with his wife Pauline of CURE, Pius Nyakayiro of GNPDR

Prison Fellowship Rwanda’s goal is to facilitate victims and perpetrators to reach a frame of mind where forgiveness and reconciliation [are] genuinely embraced.

NURC’s Mission Statement is:

To Promote Unity, Reconciliation, and social cohesion among Rwandans and build a country in which everyone has equal rights and [is] contributing to good governance.

The Vision Statement is by President Paul Kagame:8

“My vision of Rwanda is a united country that feels itself integrated into the Sub[-Saharan] region [East Africa] Family of Nations, a country that is developed and has eradicated poverty, a country that is democratic, and above all, a stable country at peace with itself as well as with its neighbors.”

I shall return to the work of both entities in another dispatch.

Gacaca Courts

The first panel of the International CURE Conference, May 21 – 25, 2018, that brought us to Rwanda was named “The Journey to Restorative Justice – Rwandan Experience”, and featured Bishop John, (Brigadier General) George Rwigamba, a member of NURC, and an Anglican priest, Rev. Antoine Rutaysire, former Vice President of NURC. Panelists indicated that between 2002 and 2012, when discontinued, the Gacaca Court way of doing justice was reprised from pre-colonial times due to the overwhelming numbers of persons in prison for perpetrating the genocide (130,000 by 2000), who, if tried by Western legal standards, would languish in prison an impossible 200 years or more! There were over 12,000 such Courts established nationwide, designed to promote communal healing and rebuilding in the wake of the Rwandan Genocide. Over 1.2 million cases were tried nationally. The Wikipedia article highlighted above states:

Because Gacaca’s original purpose was not to handle crimes at the level of severity as those committed during the genocide, the punishments associated with determination of guilt often do not fit the crime and require further proximity and intimacy between the perpetrator and victim. Despite its restorative nature, Gacaca is a legal process and with this in mind punishment constitutes a major element of the Gacaca courts. Perpetrators found guilty are sentenced to some form of punishment, but it is important to note that this rarely takes the form of a jail sentence and instead demands tasks such as the rebuilding of victims’ homes, working in their fields or other variations of community service.[13] Thus, despite Gacaca’s clear punitive and legal elements, in many ways the nature of punishment remains within a restorative framework of repairing the harm done through practical measures. (emphasis added)

There are however many challenges to the government’s claims of overall success, including:

no right to a lawyer, no right to be presumed innocent until proven otherwise, no right to be informed of charges being brought against you, no right to case/defense preparation time, no right to be present at one’s own trial, no right to confront witnesses, no right against self incrimination, no right against double jeopardy, no right against arbitrary arrest and detention, and furthermore, there is vast evidence of corruption among officials.[7][11] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gacaca_court, (last accessed June 16, 2018)

Furthermore, crimes committed by advancing RPF (Rwandan Patriotic Front) forces under the current government were exempted from the Courts, with consequent impunity drawing obvious criticism for such inconsistencies. That said, during and in the aftermath of the chaotic horror of genocide, and continuing for some years, the RPF in liberating the country (Liberation Day celebrated on July 4, and Independence Day July 2 this year) often did not even know who the enemy was. Raiders from the DRC (Democratic Republic of the Congo) repeatedly spewed their savage hatred across the border in continuing sorties of unspeakable brutality.

Were there revenge killings by the RPF? No doubt, concludes Human Rights Watch. They also conclude that given their not knowing who the enemy was, as many as 30,000 (conservative estimate) may have been murdered by the RPF; that these (too often indiscriminate) murders were at minimum tolerated up the chain of command; and that the U.N. and the U.S. in particular suppressed this information for highly questionable reasons, not least to continue to protect, as the saying goes, “their own asses” — for the dismal failure of the international community, in particular in the West, to intervene before, during, and after the genocide.

Where does that leave one? Without question, war is ever and invariably about commission of atrocious acts of mayhem and murder on a vast scale. And the RPF typically did its share. (How the brilliant St. Augustine could have imagined a “Christian Army” fighting for the Roman Empire that would kill “christianly” with love in its collective heart for the enemy is beyond comprehension. One need only read about the scientific study of Killology to appreciate that sheer impossibility!)

The United States of all nations, addicted to the twin myths of American Exceptionalism and Manifest Destiny, and perpetuated to this day by Christian leaders of all stripes, since its founding has regularly perpetrated crimes against humanity. In its Holocaust against Indigenous People early on, as well its slave trade and slavery that initially (and ever subsequently against their descendants) brutalized as many as 11 million Africans, and has also ever since on a great variety of fronts and ways been savagely ruthless in its quest for domination and wealth, it has committed vast lèse majesté against and inversion of the teachings of Jesus. Historian Peter Kuznick for instance discusses this with reference to such crimes by the U.S. during WWII and since.

Canadian veterans successfully saw removed from the War Memorial in Ottawa all reference to the deliberate carpet bombing of civilians in more than 40 German cities as much to destroy infrastructure as precisely to incite terror amongst civilians, including fleeing refugees (according to military historian Tami Biddle. The promotion of “terror attacks” in Germany was a direct order from Sir Arthur Travers (known as both “Bomber” and “Butcher”) Harris and Sir Winston Churchill.) And of course the U.S. carpet bombed over 80 Japanese cities, killing indiscriminately up to 50% of citizens, then dropped two atomic bombs inside 3 days that committed instant mass slaughter of almost 200,000 civilians…

These were in sheer numbers gargantuan crimes against humanity on a scale that makes RPF killings pale by contrast – though no less reprehensible. And two (multiple) wrongs never make a right…

The above however is incomplete without mention of what one reads in noted historian Alfred McCoy’s description of what is being developed by the American Empire, almost as if this latest Empire as it unravels across the globe is determined to take the entire Planet with it — to destroy the Earth in order to save it…

Furthermore, with reference to the gacaca courts, the Western legal system so often favours the wealthy elites over against the other-ethnic and poor, such that it is a truism that there is one law for the rich, another for the poor: justice being largely what one can afford. Western law too often is like a cobweb: it catches the little bugs but the big ones tend to get away! Further, Western law generically in fact is not about any kind of meaningful doing of justice (which biblically invariably is restorative), one that lifts up the victimized and punishes then re-integrates into society those who do wrong. Rather, as American Justice Wendell Holmes observed a century ago, our system is not about doing justice, rather it is about playing the game according to the rules. And of course it is wealthy elite interests that make the laws in the first place, above which the elites themselves so often fly. And the best players at the game called justice are the best paid/are in the employ of the wealthy elites. Finally, the Western criminal justice systems historically are generically punitive/retributive with sole concern about perpetrators, not restorative/transformative for those victimized and those who did wrong. (There is a voluminous amount of material about this on the website, in part here, and here.)

Perhaps then we in the West should be careful about casting the first stone, about pointing out the mote in the other eyes before dealing with the beam in ours… Further, it is widely acknowledged that in the extreme exigencies of post-genocide Rwanda, there was no remotely viable alternative. As one author notes:

Based on these discrepancies a definite answer about the success of gacaca courts cannot be provided. This, however, does not indicate a failure of the gacaca courts. The courts addressed several issues and without this approach the large numbers of prisoners could not have been dealt with. Justice has been exercised as well as possible in a post-genocidal society. The gacaca courts have also empowered victims by listening to their narratives. Further, victims had the power to grant forgiveness which increased the likelihood of recognition of the perpetrators by their societies. In addition, the culture of impunity has been eradicated [except sadly for RPF government forces] which decreases the risk of long-term security threats. According to surveys the degree of cooperation and therefore the need for recognition enjoys a high degree of fulfilment. However, many Hutus and Tutsi still distrust each other. The results of this dissertation point towards a limited fulfilment of the basic human needs of Rwandans. Undoubtedly, negative peace is still preferable to open violence, however, positive peace is necessary for a stable future for all Rwandans. Finally, one should remember that the genocide happened only 18 years ago – less than a generation – and reconciliation takes place in the hearts and minds of individuals and cannot be orchestrated or even dictated. Gacaca courts have led the Rwandans on the right path, but there is still a long way to go. (Gacaca Courts and Restorative Justice in Rwanda, E-International Relations, Thomas Hauschildt, July 15 2012. (last accessed June 17, 2018) ).

Conclusion

We have heard repeatedly that modern-day Rwanda is a fragile work in progress. But we have heard repeatedly about Hope as well – one that the Apostle Paul says “does not disappoint” when anchored in Christ. “Hope” in Greek Tragedies was ever the Trickster like the North American indigenous Raven or Coyote. Just as there emerged Hope that all seemed to be turning towards the good, disaster would strike and Hope would be dashed. Not so says Paul is the Christian Hope! This is reminiscent of J.R.R. Tolkien’s neologism: eucatastrophe. In the Epilogue to his philological essay On Fairy-Stories, we read that the Gospels contain a “fairy-story” with all the trappings of that genre. Only, Tolkien asserts, this Story just this once entered the stream of real human history. He writes (as seen above):

In [a true fairy-story] when the sudden ‘turn’ [Tolkien calls this a eucatastrophe – promise of “the happy ending”] comes we get a piercing glimpse of joy, and heart’s desire, that for a moment passes outside the frame9, rends indeed the very web of story, and lets a gleam come through…10 The Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories. They contain many marvels… and among the marvels is the greatest and most complete conceivable eucatastrophe. But this story has entered history and the primary world; the desire and aspiration of sub-creation has been raised to the fulfillment of Creation. The Birth of Christ is the eucatastrophe of Man’s history. The Resurrection is the eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation. This story begins and ends in joy. It has pre-eminently the ‘inner consistency of reality’. There is no tale ever told that [people] would rather find was true, and none which so many sceptical [people] have accepted as true on its own merits. For the Art of it has the supremely convincing tone of Primary Art, that is, of Creation. To reject it leads either to sadness or to wrath (emphasis added).

So in that Hope, captured in the biography of Bishop John by the title, Jesus: Hope of the Nations, Rwanda may continue to strive towards national resurrection. With no one left behind! Amen.

§§§

Next Dispatch: Reconciliation Mandate

Dispatch 3: Reconciliation Mandate

Introduction

There is indeed a vigorous and pervasive “Reconciliation Mandate” in Rwanda, from the government, the churches, and the NGOs. Below, some experienced highlights.

Sociotherapy Circles

The sun was already in its downward arc as we approached the group of Rwandan women seated in a circle on the grass above their village. Here in Rwanda, just south of the equator, it is dark every day by 6:30 p.m. We had arrived later than expected, after a bumpy ride over a country road of deep crisscrossing fissures carved by the pounding rains of the previous long Wet Season. But since early June we have basked in sunny skies and balmy mid-20s Celsius temperatures: the Dry Season norm. We had driven to the southern province of Rwanda, escorted by PFR worker Jeannette Kangabe. It was in this region in the city of Muhanga, that detailed plans for genocide had been developed. We were late, but this was African time… Delightful!

We eventually continued by foot down the goat trail towards the women, a path traversed about two hours later by school children returning home in the soon-gathering dusk.

As we neared, the women stood up as One, burst into a song of praise (we later learned) and invited us thereby into the Circle. We were caught as much by surprise as by tingling gratitude at their joyful display of heartfelt welcome.

The back story?

Prison Fellowship Rwanda (PFR) in concert with the government body called National Unity and Reconciliation Commission (NURC) both mentioned in the second Dispatch above, involving as well the Anglican Church (Diocese of Byumba), and the Rwandan agency Duhumurizanye Iwacu Rwanda (“Comfort Each Other in One’s Neighbourhood”), began implementation of the Community Based Sociotherapy Program (CBSP), that ran from 2013 to 2016, and spread over eight districts – two programs per province. (There were earlier very successful pilot projects). Ten to fifteen persons per Group participated, two trained facilitators leading each. The Program was funded by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The Groups lasted fifteen weeks.

It was in fact a further development and adaptation to Rwanda of the work of Cora Dekker – a Dutch sociotherapist with years of experience in practicing sociotherapy among traumatized refugees in clinical settings in the Netherlands. She was also the technical advisor.

There were six phases each group was guided through:

- Safety

- Trust

- Care

- Respect

- New rules

- Memories

There were as well six principles:

- Interest

- Equality

- Democracy

- Participation

- Responsibility

- Learning-by-doing

The CBSP was designed to not only fill relational gaps after the gacaca courts process terminated in 2012, but to both continue and in many ways improve upon the outcomes of same.

At project conclusion, there had been 26,730 participants and 1,823 sociotherapy groups. There had also been a total of at least 512 trained community member facilitators, 8 prisoner member facilitators, and 46 trained community members to work in Congolese refugee camps.

A succinct summation of the groups came from one of the participants:

Mvura Nkuvere (Kinyarwanda) meaning, You heal me, I heal you.

Further, many sociotherapy groups decided to continue to meet after they had finished the fifteen weeks of training. Some groups organized continuing group discussions, while others engaged in income generating activities. 68.4% of the socio-groups that started between March 2014 and June 2016 continued to meet either on a weekly or a bi-weekly basis. 57% of all the groups have started a joint cooperative or saving association (N=1294).

The cooperatives and saving associations indicate that sociotherapists and participants at a grassroots level gradually took responsibility for and ownership of the sociotherapy activities and outcomes. It is CBSP’s belief that this level of ownership and the degree of mutual trust that has been built in the groups make socio-economic development more sustainable. In addition, there is a spin-off to the wider community. In numerous cases, community members join the socio-economic initiatives of the sociotherapy groups. Local authorities support the group initiatives. In a number of districts, they assist the groups by providing financial means to invest in for example livestock.

In one district outside Muhanga in the southern province, the entire community committed time, money and labour towards a genocide memorial and research centre. We toured the not-yet-completed facility, which includes a museum and genocide research capabilities. It is at once deeply disturbing yet hopeful with full community investment.

The sun’s downward slide was nearing its end as the circle of women prayed and sang us on our way back up the trail. Stories of deep pain, healing and hope had been spontaneously shared. Since this group’s initial training in 2015, it continues to meet every Thursday for about three hours. Wishes were expressed that Jeannette would visit them more frequently… Part of us, the first Mzungus to ever visit, will somehow keep going back…

After all, we’re part of the circle now.

Reconciliation Villages: Prison Fellowship Rwanda

Jeannette sharing; Joshua Magaba of GNPDR translating

Rain falls gently as Frederick, standing just outside our covered shelter, gives his barebones testimony. He was 26 when the genocide started. The roads to escape the village were blocked. He found victims hiding in the sorghum fields and killed them.

I was in prison for 9 years. Two pastors came into prison and took us through a journey to know the value of a human and journey of repentance. First to God, then victims, then the country as a whole. The President released us. Then we went in front of victims and admitted and repented. It was very hard.

Jeannette speaks next:

On April 8th they killed my parents; I was 16. I lost all my relatives. We went into exile for two months to hide. I hid in the toilet (bathroom). After we were freed I wanted to die. When the president released the prisoners, we were so afraid. Pastor came and told us [that the men who had been released would be coming back to our village.] When we saw them, we were in great pain, a day of tears. We sat across from each other. The time came when they confessed and showed us where the bodies were. We took time to pray and get close to God. Now I am not afraid. When I have to go away I leave my children with him. The wives of those who [did the killing] didn’t believe it. We weave these baskets together and talk. Now they believe. We have come back to life. We are not worried. Please communicate what happened, that it was real.

Then it is Claudine’s turn:

I was born of those who were victims. I asked why they survived. They hid, and then fled to Burundi. Those who committed the crimes confessed to my parents. Now the wives weave together. As kids we also meet in clubs and play games together. We thank our government.

And finally, another teen explains:

Every day my mother was taking food to a place I didn’t know. Finally, she explained that my dad was in prison. She explained that he killed Tutsi. I asked her why. She explained that Tutsi have long noses….(ethnic differences). My father came back. Now we don’t have any Tutsi and Hutu, we are in clubs and we dance together.

(The above was written by fellow 2018 International CURE Conference attendee, Chaplain Hans Hallundbaek, UN NGO representative for CURE international and the International Prison Chaplains Association (IPCA – see also here), together with Rev. Cathy Surgenor of the Hudson River Presbytery, for the Horizons national magazine of the Presbyterian Church (USA), and granted permission to use here.)

These were the witness statements we heard on a visit during the International CURE Conference to Mbyo Unity and Reconciliation Village, one of eight such in existence established by PFR. What began as experiment in a pilot project in 2003, now houses over 4,000 families in both categories of survivors and perpetrators.11

We visited them as a group during the Conference, and Esther and I in staying on visited them a few more times. We in fact toured 20 new homes just constructed at one village. (Esther did a training on hygiene and sanitation for the families about to move in). We visited. We conversed. We observed… To our awareness, there is nothing of its kind elsewhere. The pilot project of fifteen years ago was an incredible success, and has given rise to ever-expanding initiatives. Other countries have sent delegations to learn and possibly replicate.

In “A Post-Genocidal Justice of Blessing as an Alternative to a Justice of Violence: The Case of Rwanda” (published in Barry Hart (ed.), Peacebuilding in Traumatized Societies, Lanham: University Press of America, 2008, pp. 205- 241.), scholar and friend Vern Redekop juxtaposes a “Justice of Blessing” with a “Justice of Violence”. He draws on his doctoral thesis-turned-book (introduced by Archbishop Desmond Tutu) From Violence to Blessing: How an Understanding of Deep-Rooted Conflict Can Open Paths to Reconciliation (Ottawa: Novalis, 2009).

Vern, drawing in turn on the groundbreaking work of anthropologist (and so much more!) René Girard, states concerning a “Justice of Blessing”:

Expressed simply, a justice of blessing is a structured way in which perpetrators commit themselves to take action diachronically [over the long haul] for the well-being of the survivors of their genocidal actions.

… when mimetic [imitative/imitated] structures of blessing infuse a relational system, people work toward the mutual well-being of one another. I am told of how [in pre-colonial times], at the village level in Rwanda, this was often the case; Hutus and Tutsis lived together with little regard for distinctions between them.

He contrasts this with a “Justice of Violence”:

The story is told of someone who went on to the afterlife and wanted a tour of the premises. She wanted to see hell first. She found grumbling, unhappy people who looked as though they were starving. There were tables of food in front of them but their forks were longer than their arms so they could not get the food in. She went on to heaven where she found happy, well-fed people. The tables of food were the same as in hell as were the long forks. The only difference was—they were feeding each other…

This story illustrates the difference between mimetic structures of blessing and mimetic structures of violence. In this fictional heaven people were contributing to each other’s well-being;… (emphasis added)

Vern is describing exactly what is happening in these amazing villages. Of course “Hell” is the direct inversion. Theologically: if “God is Love”, Hell is the Expulsion of Love.

At one point in Vern’s superb paper – that I encourage all to read! – he emphasizes that there are three overarching prerequisites to building and buttressing a Justice of Blessing, one of which is that

in the face of large scale violent events, the various sub-processes need to take place within institutions that could include Truth and Reconciliation commissions. If there is to be a justice of blessing, this could demand an institution within which there is on-going follow-up.

In a prolonged discussion with Bishop John Rucyahana (I’ve mentioned him often in earlier “Dispatches”), I compared post-genocide reconciliation work in Rwanda to post-apartheid reconciliation work in South Africa. The Bishop indicated he was indeed respectful of the work done in South Africa since the end of apartheid.