By George Yancy, Truthout

Published March 5, 2021

photo above: yankeewikis.com

WN: I first became involved with men in prison in 1974, at a time the first prison I visited (Oakalla Prison, Burnaby BC, Canada) still operated under a military regimen with many ex-military hired as guards; with an ex-air force serviceman as chaplain who liked telling stories of his martial arts prowess; and a shadowy group operated a kangaroo court to discipline those not/too-lightly punished by their superiors–“kangaroos” who too told stories of bravado and revenge. . . Like when four guards extracted a prisoner from the “hole” because he’d thrown a bucket of urine at one of them, and proceeded to beat the living s_ _t out of him. . .

A fellow seminarian at the time, whom I had helped get his first job at Oakalla as a guard, as a newbie was summoned one night to keep watch in case the “IC”–in charge of the prison that night–might suddenly appear down the hall. . . When I suggested my friend should report the incident to his superiors who might care(?), he wouldn’t/didn’t. . .

During the next few months I watched my friend turn, until for all intents he stopped being my friend; and started before that telling his own stories of how good it now was to know the guards always had his back. . . Until he told me after getting married that he dreaded having a son, for fear the son would one day find his way to prison. Until the marriage fell apart after the birth of a daughter. . . Until he changed his career, moved to Ontario, to one helping, not harming, others as an ambulance driver. . . Until. . . I don’t know. I sadly never heard from him again. . .

In the 40 subsequent years of prison visitation (and still gratefully engaged with many “returned citizens”), of hearing thousands of times the clanging doors shut and the multiplied voices and testimonials of their keep; after a career retirement following 16 years as Executive Director of the same prison visitation/Restorative Justice Program that took me first to jail; I could still largely only imagine myself into the experience of being a prisoner. . .

So much less, can I imagine myself into the experience of being Black/minority ethnic in a white supremacist world. . .

All I can do for starters is (try at least to) listen. . . Still. . .

So please listen. . .

excerpts:

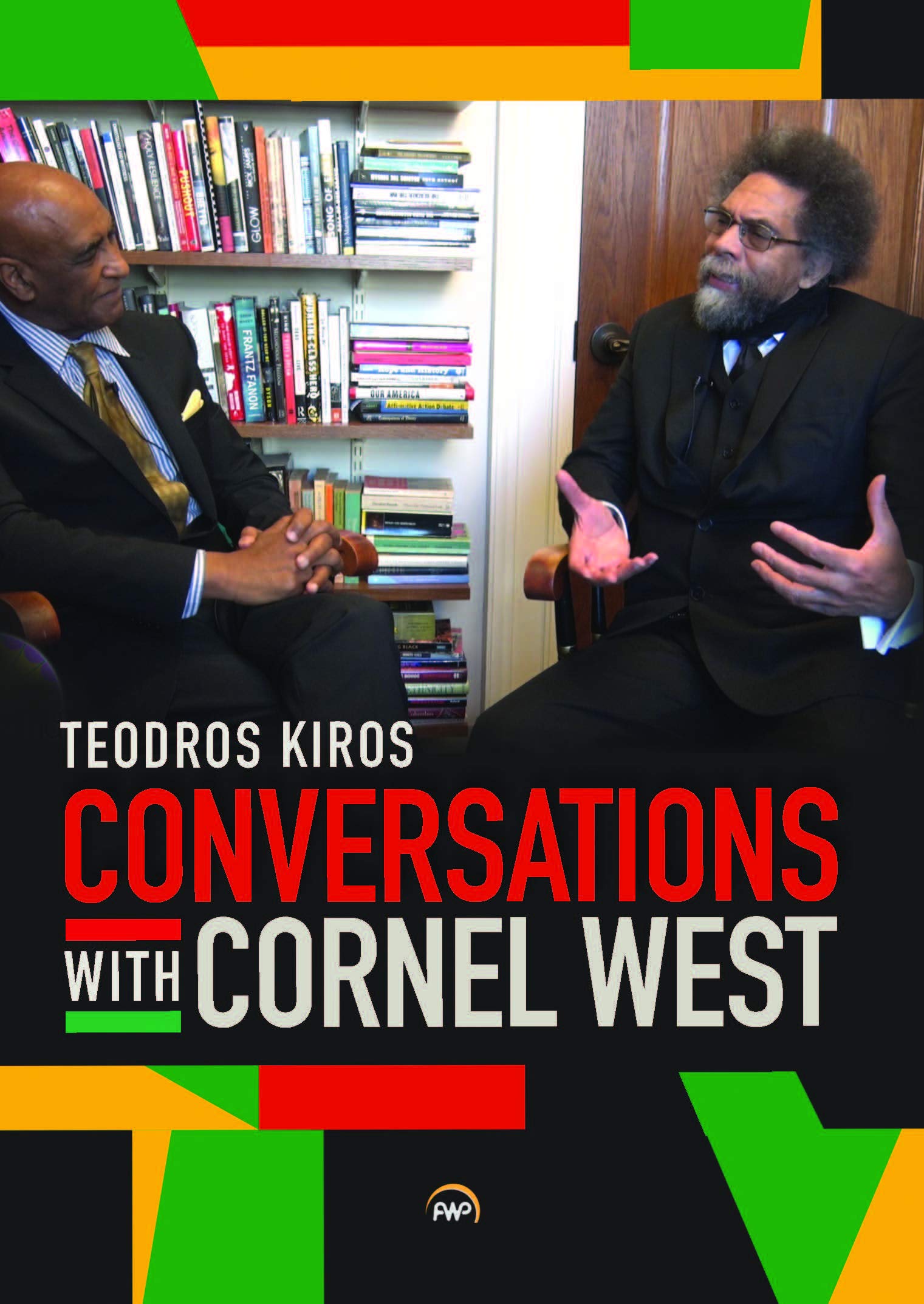

Cornel West is a preeminent public intellectual, a brilliant philosopher-gadfly and a towering thinker whose critically engaging voice and fearless speech have proven indispensable for calling out injustice wherever it exists. He is a force grounded within a prophetic tradition that refuses idols, even if that idol is democracy itself. He is a bluesman who grapples with the funk of life through a cruciform of love within a crucible of catastrophe, where despair never has the last word.West isn’t a typical professional philosopher. As a professor at Yale in the mid-1980s, he was arrested for attempting, through protest, to get the university to withdraw its investments from all companies that were doing business in Apartheid South Africa. And he relentlessly exposes the limits of disciplinary smugness and the hypocrisy of epistemological “purity.”

West is arguably the most publicly visible philosopher in contemporary America, but despite his prominence and brilliance, he was recently denied the option of being considered for tenure at Harvard, where he currently teaches, and where he had previously held tenure.

…

George Yancy: I was surprised and disturbed to hear about your situation at Harvard University. It is my understanding that a faculty committee was reviewing your renewal and that committee asked that you be considered for tenure. Yet, that consideration, as I understand it, was denied. I immediately thought about forms of academic institutional fear when it comes to maintaining scholars — especially Black scholars and scholars of color — who engage critically in processes of calling academic insularity into question, calling empire into question, calling forms of institutional and systemic injustice into question. Given your conceptualization of vocation as tied to a form of calling that allows suffering to speak, I immediately thought about how certain institutions might care more for their self-image and their donors as opposed to keeping scholars who cause “good trouble,” as that towering figure, the late Congressman John Lewis would say. Some may very well fear the vocational work that you do so well, with so much fire, courage and love. Talk about how you understand the distinction between vocation and profession.

…

Artwork below: “Mama,” icon by Kelly Latimore

It’s revolution in the spiritual sense, revolution in the political sense and revolution in the economic sense, which is a massive transfer of power, of respect, of wealth. It is a transfer that is not about putting others down, but it’s a democratizing, it’s a sharing of that respect, the sharing of that wealth, the sharing of those resources and so forth. So that radical democratic end is informed by this intense commitment to vocation, finding voice, but always situating your voice in relation to a certain tradition, or what Antonio Gramsci called a “critical historical inventory.” That’s Socratic, it’s self-examination.

But all of us are always already in circumstances not of our own choosing, and so we have to situate ourselves in particular historical traditions, and my traditions come from the magnificent West family, Clifton and Irene West, from the Shiloh Baptist church, and from the Black radical tradition. But it also comes from the best of my teachers, Hilary Putnam, John Rawls, Tim Scanlon, Thomas Nagel, Richard Rorty, Martin Kilson, Preston Williams, one can go on and on. So, I am a fusion, I am a hybrid of the best from whence I come, and the best of my formal education, but all of them are just feeding into a particular vocation and witness, an intellectual vocation and a prophetic witness.

…

This is how you use the term kenosis, which is a form of emptying. I agree with it and use it in my own work.

Yes! It’s kenosis in that very deep sense. That’s why I’m always pulled by the great artists of kenosis. It could be Rembrandt’s The Return of the Prodigal Son, which is kenosis on the canvas, the emptying of the self, of father to sons. Or it could be James Brown on the stage, the emptying of himself for four hours straight, nonstop; it could be Aretha Franklin behind the microphone, the emptying of herself. That is kenosis at work.

…

So, if I put my cemetery clothes on every day, if I’m coffin-ready every day, it means a particular kind of catastrophe, like physical death, is always already there on a continuum with the other forms of death. And to be a Black man in a white supremacist civilization, where Black love is a crime, where Black hope is a joke, where Black freedom is a pipe dream, and Black history is a curse, then I’ve got to fight that no matter what. So, I’m going to love and be willing to be criminalized. I’m going to fight for freedom and be willing to be crushed. I’m going to try to provide some kind of hope and be willing to be laughed at as a joke.It’s revolution in the spiritual sense, revolution in the political sense and revolution in the economic sense, which is a massive transfer of power, of respect, of wealth.

So, one is radically cutting over against oneself. And then when you add the cruciform character and the tragic-comic content to it, it means that you’re in but not of this empire, you’re in but not of this white supremacist society, trying to be in but not of this predatory capitalist society, you’re in but not of this patriarchal, homophobic society, but you know all that’s inside of you, too. And that is part of the paradox, the white supremacy that is inside of me. I grew up within a patriarchal empire, so I’m going to have the patriarchy in me. So, I have to fight that every day. That’s part of learning how to die. That needs to die daily in order for me to emerge as a stronger love warrior, freedom fighter and wounded healer.

…

My particular voice is one that has been deeply shaped by critiques of empire, predatory capitalism, and white supremacy in the ways in which all of these are interwoven. But what makes me a little different from some of my brothers and sisters is that I tend to look at the world through the lens of the cross, through a moral and spiritual lens. So, I’m very tied to the prophetic voices of Hebrew scripture. I view Hebrew scripture as one of the great moral revolutions in the spreading of hesed, which is a steadfast love and loving kindness of orphan and widow, the hungry, and the shelterless, the homeless and the oppressed.

So, when the Palestinian Jew named Jesus goes to the Temple, which is the largest edifice east of Rome, with hundreds of Roman soldiers, bankers and intellectuals, and the chattering classes, and runs them out, well, that is very much like running out elites in the White House, Pentagon, Congress, Hollywood, Wall Street, Harvard, Yale, Princeton and Emory. And you’re running them out not because you’re demonizing them, but because there’s too much callousness and indifference toward the poor that you see in their way of life.

You see too much commodification that makes their souls too cold and their hearts too coarse. There’s too much bureaucratization that distances them from the lived experience of people who are trying to struggle. There’s too much white supremacy in terms of its mistreatment of precious Black people and Brown people and so on. I’m much more explicit about the cross and the Christian tradition. Many of my precious brothers and sisters within the philosophical tradition, Black or what have you, swerve away from that particular Christian stream and strand. And that’s fine with me. It’s a matter of our voices bouncing up against one another yet again.

…

Your work, as a public intellectual, engages not just a specialized few, but aims to intervene within a larger conversation that has implications for the destiny of large numbers of people. I think that this vision puts you at odds with certain neoliberal assumptions within academia. This is the work that you do. Whether you’re discussing the precious lives of our Palestinian or Jewish brothers and sisters, you’re asking across the board for all of us to empty, to undergo kenosis, in relationship to all forms of corrupt power and domination. And within academic spaces, you’re also calling into question forms of corruption, bureaucratization, neoliberalism and hegemonic power. I see you as an indispensable gadfly within that space. So, how do you understand what is going on at Harvard with respect to not even wanting to consider you being considered for tenure? How do you see the voice that you’ve developed and nurtured, the vocation that you’ve chosen, the gadfly that you are, in relationship to your situation at Harvard? Is there not an important relationship or tension here? Do you not see this as part of the problem?So, one is radically cutting over against oneself. And then when you add the cruciform character and the tragic-comic content to it, it means that you’re in but not of this empire, you’re in but not of this white supremacist society, trying to be in but not of this predatory capitalist society, you’re in but not of this patriarchal, homophobic society, but you know all that’s inside of you, too.

…

A little crisis of the professional managerial class of Black folk, yes, it’s important, but it still pales in the face of the catastrophes of our brothers and sisters who constitute the masses of Black and poor working people. We always have to work with what we have, and we have to use what we have in order not to sell our souls for a mess of pottage. The saddest thing that happens is when those folk who adjust to injustice then parade around as a success. We’re talking about greatness here.

Greatness does not adjust to injustice. It doesn’t adapt to indifference and then pose and posture as if that is success. Not at all. The worst thing that could happen is that young folk think that it’s just about getting into the academy to be successful, become the next wave of peacocks. That’s not what it’s about at all.

…

So, I would hope that my example, given all of my privileges and all of my blessings, will communicate the message that young people should be fortified. Don’t be disrespected. We come from a great people. Black people are a world historical people whose gifts have disproportionately shaped the cultures of the world. And there’s just no doubt about that, so you’ve got to be true to that, and you are true to that with your humility and your tenacity. And you have to be willing to speak the truth — to the powerful and the powerless.

When Harvard treats me in this way, that’s a sign of its spiritual and intellectual bankruptcy. Now, it could bounce back, but you have to call it for what it is. You have to acknowledge that there’s new styles of Jim Crow in the life of the mind and the country. It’s just a fact.

…

You look at The New York Review of Books. Thank God there are brilliant essays by brother Brandon Terry, but other than Darryl Pinkney and Anthony Appiah, it has basically been a case of Jim Crow. How many of your books, how many of John Hope Franklin’s books, how many of Houston Baker’s books, how many of Hortense Spillers’ books have been reviewed? Intellectual work that’s taken place in the last 40 years has been rendered invisible because of the Jim Crow quality of the ways in which they review books. And that’s just one example.Greatness does not adjust to injustice.

We have to be honest about that and say that we can do better. And we must do better. And, in fact, if you subtract the number of Black people in the Department of African and African American Studies at Harvard and only include Black folk in other departments, Harvard looks like the National Hockey League. There’s hardly any Black folks at all. That’s how Wall Street looks. That’s how elite formation looks. That’s how Silicon Valley looks, especially at the top.

You see, that’s still Jim Crow, new style. So, when people say, “Ah Brother West, you are so hard on Harvard, you’re so hard on the professional managerial class,” I say, “Come on.” I’m not even beginning to tell the truth in terms of allowing this suffering to speak. Yes, let’s pursue veritas. Let us take veritas seriously, the motto of Harvard, and see its own weak will to truth about itself. That’s the best kind of witness that becomes very important. Not in a spirit of hatred or revenge. This is Coltranean all the way down. This is a love of truth, a love of beauty, a love of goodness and a love of the Holy for those of us who are religious.You see, that’s still Jim Crow, new style. . . Yes, let’s pursue veritas. Let us take veritas seriously, the motto of Harvard, and see its own weak will to truth about itself. That’s the best kind of witness that becomes very important. Not in a spirit of hatred or revenge. This is [John] Coltranean all the way down. This is a love of truth, a love of beauty, a love of goodness and a love of the Holy for those of us who are religious.

…

And it just means that the class hierarchy is more colorful, and the imperial hierarchy is more colorful, but people are still suffering. King comes from our tradition, brother. He’s a wave in our ocean. You and I know about 400 years of being chronically hated and yet we keep dishing out love warriors like Martin Luther King, and Stevie Wonder, who’s thinking about going to Ghana. Four-hundred years of being terrorized and yet we keep dishing out freedom fighters like Fannie Lou Hamer. Traumatized and yet we keep dishing out wounded healers like Aretha Franklin. That’s a great people with a great tradition. We’re human beings like everybody else, but I’m talking about the best of who we are. So, when we think of a Martin Luther King, we say, “What would the analogues in the academy look like? What would the intellectuals look like if they were fundamentally grounded in those traditions of love warriors, freedom fighters and wounded healers?” I think that is our challenge.

…

And it isn’t easy, because we have this lingering Trumpian, neo-fascist moment.

Right, but neofascism is not new to us. Not new at all.

We are bluesmen and women and we are never, ever surprised by evil, we are never ever paralyzed by despair.

Please click on: Never, Ever Surprised by Evil