In a new book Dream Hoarders, Richard V. Reeves argues that members of the upper middle class, not just the ultra-wealthy, are making our society profoundly unequal.

By Bryce Covert

JULY 3, 2017

WN: What the author calls for in the article highlighted below is what biblical Jubilee Justice repeatedly heralds: that for everyone “enough should be truly enough”, as acclaimed Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann argues in the article hotkeyed¹. There is no meritocracy in God’s Kingdom! There are no prisoners taken in a free market system.

Creation like grace is endlessly freely given to entire humanity in super-abundant Divine munificence –

Too often, the church has understood God’s unconditional grace as solely a theological phenomenon, instead of recognizing that it has to do with the reordering of the economy of the world. — Walter Brueggemannand over against the traditional doctrine of hell, beyond death. Or as Jesus said: “He makes his sun rise on people whether they are good or evil. He lets rain fall on them whether they are just or unjust (Matthew 5:45b). One could add to Jesus’ categories to put the point home: “whether poor or rich, whether talented or ungifted, whether intelligent or slow, whether deserving or otherwise, etc., etc., etc.” And Christians are to “Follow God’s example, therefore, as dearly loved children and walk in the way of love, just as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us as a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God (Ephesians 5:1 & 2).Like the Creation, God’s Atonement (why Christ died) is not about satisfying a blood-lust in God, but about offering the same munificence of grace to all humanity throughout time and eternity!

The market [over against God’s grace] cares not for fairness, but only for efficiency. Those who play the economic game to the hilt and succeed become fabulously wealthy. Those who cannot play may starve. In its relentless drive to squeeze all it can out of society’s scarce resources, the free market takes no prisoners. In the process it generates great inequalities² (p. 27; emphasis added).

And so all Creation cries with the Revealer (6:10), “How long, Sovereign Lord?“³

“Lord in your mercy, hear our prayers!“

_______________

¹ A similar article by Walter Brueggemann may be found here. It was published in the print version thus: “The Liturgy of Abundance, the Myth of Scarcity”, The Christian Century 116, no. 10 (24 March 1999): 342-347.

² In this vein, Paul Street writes:

They [US ruling class] have no intention of removing Trump, however—not yet, at least. So what if he’s dangerously “unfit for the presidency”? Who cares if his call to “deregulate energy” is “almost a death knell for the species” (Noam Chomsky)? There’s too much quick money to be made with Trump and his opportunistic Republican allies in office. “American” capitalism is an inherently sociopathic system that exhibits less special attachment to the United States with every passing globalist year. Beneath all his ridiculous and manipulative populist pretense and his vile Twitter thuggery, Trump dutifully meets regularly with top corporate CEOs. He seems sincerely dedicated to escalating the already savage inequality of wealth and power in the U.S. Austerity, tax cuts and deregulation are good for the rate of profit (“The Notion That White Workers Elected Trump Is a Myth That Suits the Ruling Class“; emphasis added).

³ Mark Charles writes:

One of the driving factors of our neglect of the relationship between creation and humankind is our greed. We have an insatiable appetite for more and more, and this has caused a deep wound to the land. The Euro-Western world and life view is in direct contrast to that of the Indigenous peoples of North America, where the land is treated in a familial manner (“Creating a New Family: A Circle of Conversation on the Doctrine of Christian Discovery”), p. 20; found online here.

excerpts:

Pretending that people making six figures are middle class, and then promising to protect them from any tax increases, means politicians are unable to ask these families to pay a tiny tax into new universal benefits like paid family leave. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Real solutions to exponentially increasing income inequality will require extensive public investment. And the tax revenue required can’t all come from the top 1 percent. As Reeves shows, even if the top tax rate on household income over $470,700 went back up to 50 percent, where it was for the highest earners in the mid-’80s, it would only raise an additional $95 billion a year. That’s not insignificant, it’s but not nearly enough to fund things like a universal basic income, a government jobs program, universal childcare and preschool, free college, and single payer healthcare. And it’s not as if the upper middle class can’t afford to pay more. “[M]ore money can be raised from the upper middle class without plunging them into near poverty…,” he notes. “[I]f we need additional resources for public investment, it is reasonable to raise some of them from the upper middle class.”

But while the upper middle class may not see itself as a distinct group, it has an intense grip on power. Nearly 80 percent of this class can be expected to turn out for elections, as compared to less than half of the poorest Americans. Reeves also sees other kinds of influence: the cultural sway of having so many of its members working in the media, advertising, and the arts, as well as dominance in business, science, and even politics itself. “As a class, we are a powerful bunch,” he says.

He also sees this class as not just defined by income, but by better health, education, occupational opportunities, and even different family structure. The upper middle class then uses these assets to hoard opportunities for itself, perpetuating an unfair system: Its members fight to preserve zoning laws that keep the good schools free of poorer children, find ways to pay their children’s way into elite colleges (he takes particular umbrage with legacy admissions), and trade favors to get their kids into unpaid internships. The rich skew the game so that American class structure stays entrenched.

…

If Reeves is, as he says, not afraid to take on the wrath of his own class for the betterment of those with less, why doesn’t he offer bolder and more dramatic proposals? Why not propose dramatically increasing taxes on the top fifth of the country and using the money to, say, offer a universal basic income to everyone else? Just giving the poor money has been found to increase their incomes and even improve health and education. This and other policies, like universal preschool and health care, could help us create a fat middle, with many people enjoying a decent standard of living and few at the very bottom or top.

The answer may lie in the fact that for all his talk of a rigged system, Reeves doesn’t actually want to transform it. Rather than focus on improving the standard of living for all children—what economists call absolute mobility—he focuses on how children can move to a higher rung on the income ladder than the one their parents stood on. That means, mathematically speaking, there have to be children in the upper middle class who move downward to make room at the top for the children of other classes. For Reeves, American society is a zero-sum game.

Then there’s the question of whether a market can ever in fact be objective. Reeves’s biggest blind spot is any “ism” other than classism that might stymie someone’s chances of getting ahead. Perhaps the best tell on race is that he frequently quotes Charles Murray, author of a book that argues that black people are less intelligent than white people, and features a blurb from Murray on Dream Hoarders’s back cover. But he also gets the state of race and gender wrong himself. “Women and people of color are able to succeed more freely today, in part because of the slow triumph of meritocratic values,” he writes. “The meritocratic ideal is helping to dig the grave of discrimination.”

Why would he see it this way? Because he wants to preserve the meritocracy rat race. For Reeves, the problem is not that America’s system creates a competition that will always produce winners and losers; it’s that the competition doesn’t start out fair enough. “The goal should not be to reduce market competition; it should be to create more competitors…,” he writes. “[M]aterial inequalities generated by market competition are fair to the extent that the opportunities to prepare for the competition are equal.”

“Simply put, I am arguing for a meritocracy for grown-ups, but not for children,” he says.

Yet he never talks about what happens to the losers in that system. What if someone doesn’t have the “skills, knowledge, [and] intelligence” that a market system supposedly rewards? Are they to starve? Incompetent rich kids should not get ahead just because they’re rich. But the bigger problem is a society that is willing to leave you to the wolves if you don’t have “merit.” We should care about the well-being of all our fellow citizens, regardless of their supposed skills or smarts. Losing a fair game doesn’t mean you deserve nothing.

Then there’s the question of whether a market can ever in fact be objective. Reeves’s biggest blind spot is any “ism” other than classism that might stymie someone’s chances of getting ahead. Perhaps the best tell on race is that he frequently quotes Charles Murray, author of a book that argues that black people are less intelligent than white people, and features a blurb from Murray on Dream Hoarders’s back cover. But he also gets the state of race and gender wrong himself. “Women and people of color are able to succeed more freely today, in part because of the slow triumph of meritocratic values,” he writes. “The meritocratic ideal is helping to dig the grave of discrimination.”

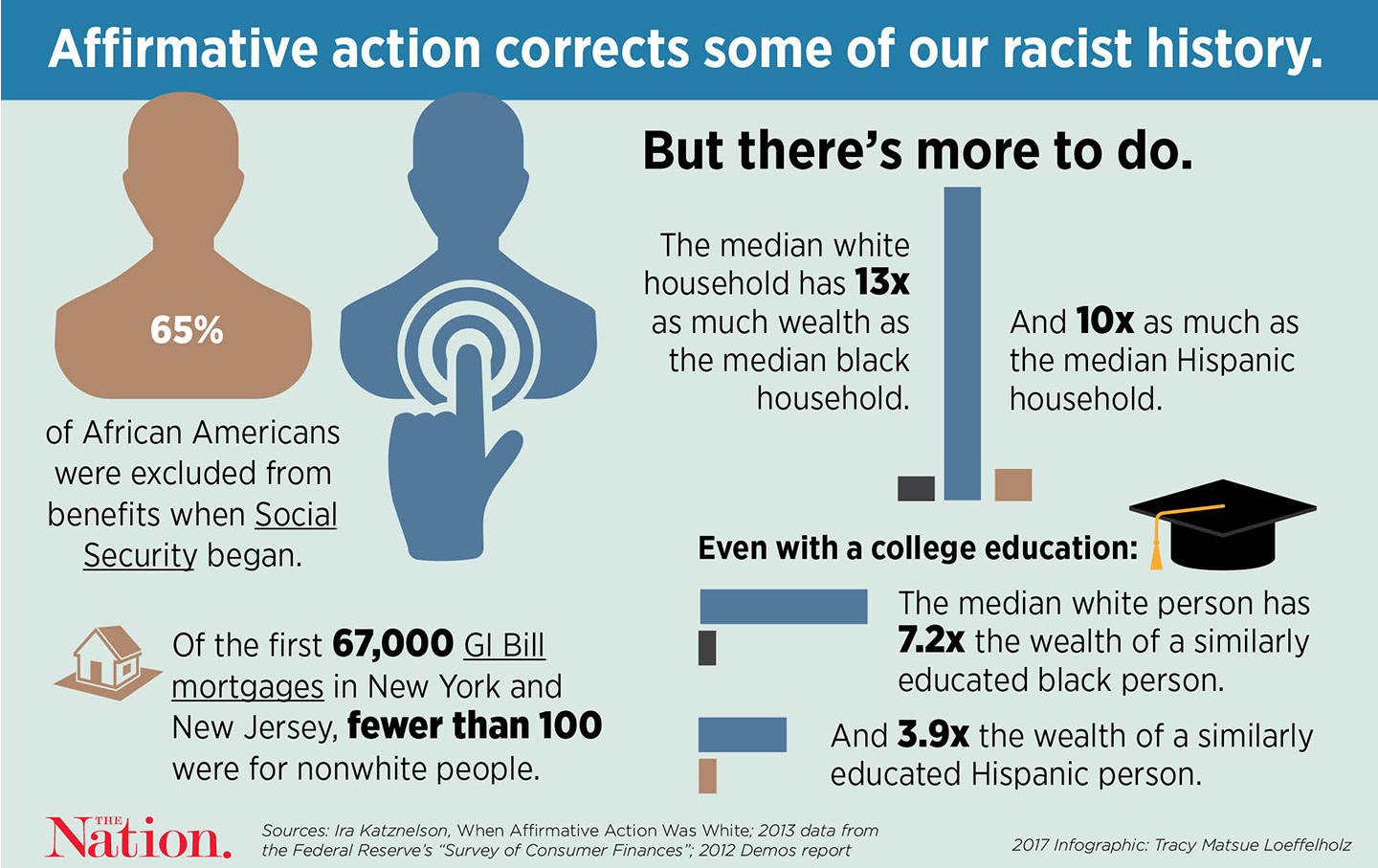

(Please click on image above for source)He’s right in part. Blacks are no longer enslaved, women and people of color have more enumerated rights, and their access to better jobs has expanded. But the idea that discrimination is on its deathbed, and the arrival of race- and gender-blind meritocracy is imminent, is ludicrous. Women make up two-thirds of minimum-wage workers and just 5.6 percent of big company CEOs, all the while still earning a percentage of what men make even while working full-time. There has never been a generation in which black children stood the same chance at economic advancement as white children, including ours, even if they become more educated and skilled; the gap between black and white wages is larger now than in 1979.

Meanwhile, meritocracy is more often to blame for perpetuating discrimination than heralding its end. One study found that when an organization explicitly calls itself a meritocracy, managers favor male employees over female ones. If a workplace, or a society, believes that all one needs to get ahead is talent, it quickly ignores anything else that might keep someone from rising.

Reeves says he wants upper-middle-class Americans like himself to pay more so that the playing field is leveled for all. But his solutions suggest he’s not willing to take that instinct very far. His class wouldn’t have to pony up very much for the milquetoast solutions he puts forward. Even after his ideal revisions, the basic structure of America’s ruthless market-based society would remain intact. In his world, being a member of the lower classes, even with more mobility, would still destine you to destitution.

Please click on: Top 20%